The Secrets Behind Diverse Boards

Four women currently serve on the board at Eagle Bancorp Montana, the $1.3 billion asset holding company for Opportunity Bank of Montana. That’s by design, says Chairman Rick Hays.

“[We] decided that we needed to have a larger board,” Hays says, after a 2012 branch acquisition doubled its footprint in Montana and prompted a later increase from seven to nine members. The Helena, Montana-based commercial bank wanted to add directors representing its expanded geography, along with younger board members and women. Maureen Rude, who joined the board in 2010, was the sole female director at that time.

“We had all the board members, all the executive officers, the local market presidents in those communities, all looking for people with the characteristics we were looking for,” says Hays. Expanding its networks worked: Two women joined in 2015, and the fourth, public accountant Cynthia Utterback, in 2019. During that time, the bank also replaced a male director with another man with a technology background.

“We’re looking for the best possible candidates,” Hays says. “If you decide what you want and commit to getting it, you can get it done.” Adding new perspectives and backgrounds benefits the board and the bank, he adds. “I firmly believe that diversity is about the best possible business decision we can make; I’ve experienced it over and over in a variety of organizations.”

Almost 60% of the directors and CEOs responding to Bank Director’s 2021 Governance Best Practices Survey believe that diversity in the boardroom improves corporate performance. However, fewer than half – 39% – have three or more board members who they’d consider to be diverse, based on gender, race or ethnicity.

The benefits of diversity in the boardroom are frequently touted by corporate governance experts, and many of the survey participants shared their experience. Here are a few of the comments we received:

“[D]iversity has helped shape everything from policies to product positioning.” – Lead director of a public bank between $1 billion and $10 billion in assets

“We have diversity in age, gender, geography, ethnicity and career experience. Creates more robust questioning when discussing products, trends, issues to ensure full vetting, understanding and ramifications of decisions.” – Independent director, public bank above $10 billion in assets

“[Due to diversity] [w]e have re-visited agendas, meeting logistics, and historical approaches to initiatives with a fresh lens.” – Independent chair at a private bank between $1 billion to $10 billion in assets

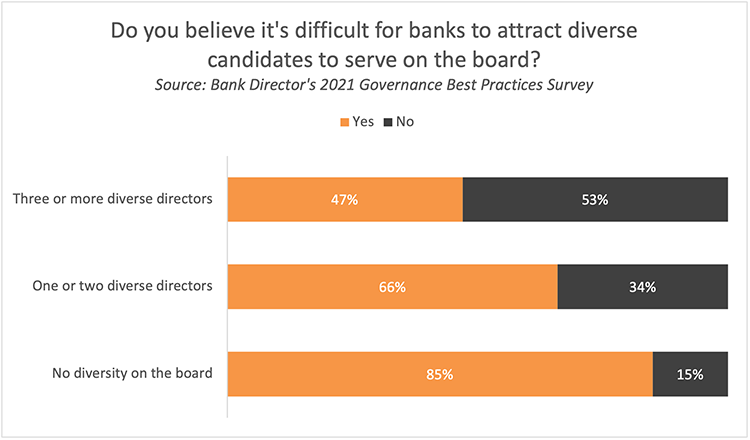

Sixty-five percent of respondents want to add more directors with diverse backgrounds, but almost as many (61%) believe it’s difficult to identify and recruit them to serve on the board. These candidates may be in high demand, but the survey finds that respondents representing more diverse boards report that it’s easier to recruit diverse candidates with the skills and expertise their organization needs.

As Rick Hays at Eagle Bancorp Montana illustrates, diverse boards broaden their networks to recruit diverse, qualified candidates. But an analysis of the habits of diverse boards yields further clues about their practices. They tend to have mechanisms in place to create space on the board, and to identify the skills and attributes they’re seeking.

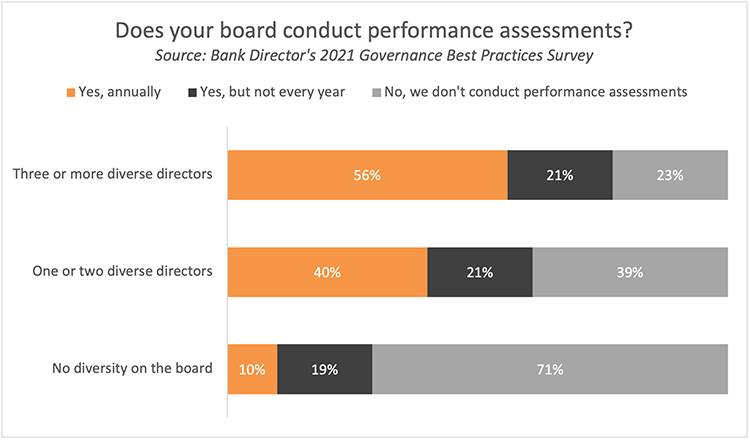

Board evaluations can be valuable tools to evaluate governance practices and identify disengaged members. The survey finds that diverse boards more frequently use and also make deeper use of performance assessments, from assessing the effectiveness of the entire board, to identifying underperforming directors and conducting one-on-one conversations with directors.

Bank Director offers a board evaluation and peer assessment through its membership program. Mascoma Bank, a Lebanon, New Hampshire-based mutual, uses this evaluation annually. Clay Adams, the $2.4 billion bank’s CEO, says the tool provides a framework for the board to assess its practices, such as ensuring that the board is receiving an appropriate level of detail about the bank’s operations.

“We’re always thinking about how to do things better,” says Adams. “We use the board effectiveness survey to make sure that we’re on the right path.”

Peer evaluations are less commonly used by bank boards – 24% say their board uses one. Respondents representing boards with three or more diverse members (36%) are more likely to use this tool.

Mascoma’s board conducts a peer assessment every other year, under the purview of the governance committee. Adams has served on other boards that used similar assessments, which he believes provide tremendous value in driving conversations with underperforming directors. “Diverse board member or not,” he adds, “if a person is not fulfilling the duties – duty of trust, duty of care, duty of loyalty – then they shouldn’t be on the board.”

Bank Director included Mascoma Bank in its analysis of the Top 25 Bank Boards for Women earlier this year; the mutual has since added two more women to its board, so its composition is now evenly split between men and women. Adams emphasizes the importance of intention in building a diverse, skilled board. “We’re constantly talking about it [and encouraging] board members to think about people they come across in their lives or reaching out to communities where we may not – as a board, as individuals – interact,” he says.

Adams hopes to further diversify the boardroom. “We’d like to have a [person of color] on our board,” he says. “We live in a predominantly white region, northern New England. Therefore, we need to work a little harder to network with people who are members of that community.”

Mascoma also incorporates term limits for directors – 15 consecutive years – and a mandatory retirement age, at 72, as mechanisms to regularly open seats on the board. These policies were last examined by Bank Director in 2020; our survey found that boards with “several” diverse directors were slightly more likely to use a mandatory retirement age or term limits.

Getting the right mix of skill sets, backgrounds and experiences results from a gradual, deliberate process, says Hays. “When we’ve filled any of our board slots, we’ve probably had discussions for a year and a half to two years to get there,” he says, due to the value Hays and the board place on its composition. “It takes time to find the people we were so fortunate to find [and] bring onto the board. We could not have done it any sooner.”