Will We Ever See Three Times Book Again?

Mergers and acquisitions are examined as part of Bank Director’s Inspired By Acquire or Be Acquired. Click here to access the content on BankDirector.com.

In the late 1990s, the economy was doing well.

Bank stocks traded at such rich multiples that no one batted an eye when a management team sold their bank for two times book. That valuation meant you were a mediocre bank.

Take Fifth Third Bancorp in Cincinnati. In the ’90s, its stock traded at more than five times book value. A well run and efficient bank, it had the currency to gobble up competitors and it did.

It announced a deal in 1999 to buy Evansville, Indiana-based CNB Bancshares for 3.6 times tangible book value and 32 times earnings. “That was not completely unheard of,” says Jeff Davis, managing director at consultancy Mercer Capital. Fifth Third announced a deal in 2000 to buy Old Kent Financial Corp for a 42% premium.

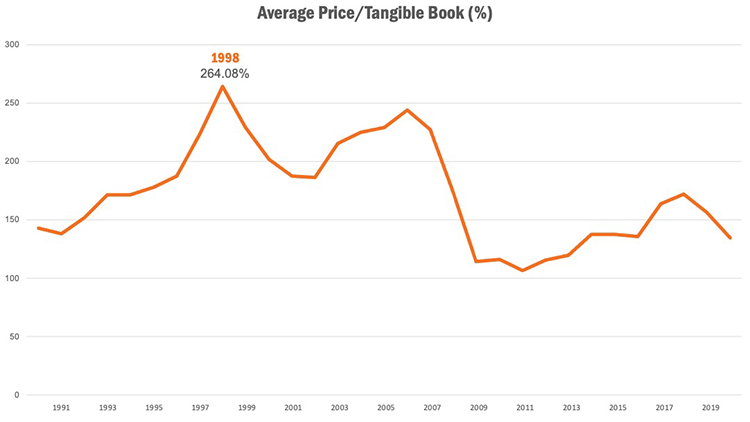

In fact, Fifth Third was a little late to the M&A premium game. The average bank M&A deal price reached a peak of 2.6 times tangible book value in 1998. The median price was 24 times earnings that year.

M&A Pricing Peaked in 1998

Source: Mercer Capital, S&P Global Market Intelligence and FDIC.

It was such a hot market for bank acquisitions, investors rushed into bank stocks in order to speculate on who would get purchased next. I remember sitting down with then-president of the Tennessee Bankers Association, Bradley Barrett, in the mid-2000s. He predicted the market would fall and many banks would suffer.

Boy, was he right. He was probably the first to school me in banking cycles.

Fast forward two decades. The industry is in a relatively depressed trough for bank valuations. Selling a bank for three times book value in the 2020s seems a remote fantasy. And it is. The pandemic and the economic uncertainty that kicked off this decade took a huge chunk out of banks’ earning potential and dragged down shares. As of Feb. 2, the KBW Nasdaq Bank Index was down 4% compared to a year ago. The S&P 500 was up 18% in the same time frame.

Granted, bank stock valuations have improved during the last six months. Investors tie bank stocks to the health of the economy: When the economy is improving, so will bank stocks, the thinking goes. As pricing improves, bankers should be more interested in doing deals in 2021, Davis says. Much of bank M&A pricing is dependent on the value of the acquirer’s stock, since most deals have a stock component.

But rising stock prices haven’t translated into higher prices for deals – at least not yet. The average price to tangible book value for a bank deal at the end of 2020 was 116%, according to Davis, presenting slides during a session of Inspired by Acquire or Be Acquired.

Improved stock valuations alone can’t alleviate the pressure holding down M&A premiums. Newer loans are pricing lower as companies and individuals refinance or take on new loans at lower rates, slimming net interest margins.

Plus, investors have also been less receptive recently to banks paying big premiums for sellers, says William Burgess, co-head of investment banking for financial institutions at Piper Sandler, during an Inspired By presentation.

There’s usually a rise of mergers of equals in times after an economic crisis, and that’s exactly what the industry is experiencing. The rollout of the vaccine and improving economic conditions could lead to more confidence on the part of buyers, higher stock prices and more bank M&A. Sellers, meanwhile, are under pressure with low interest rates, slim margins and the costs of rapidly changing technology.

“We think there’s going to be a real resurgence in M&A in late spring, early summer,” Burgess says.

To see M&A pricing rise to three times book, though, interest rates would have to rise substantially, Davis says. But higher interest rates could pose broader problems for the economy, given the heavy debt loads at so many corporations and governments. Corporations, homeowners and individuals could struggle to make debt payments if interest rates rose. So would the United States government. By the end of 2020, America’s debt reached 14.9% of gross domestic product, the highest it has been since World War II. In an environment like this, it might be hard for the Federal Reserve to raise rates substantially.

“The Fed seems to be locked into a low-rate regime for some time,” Davis says. “I don’t know how we get out of this. The system is really stuck.”