Blowing the Whistle

When it was revealed last year that thousands of Wells Fargo employees had opened millions of unauthorized accounts for customers in order to meet aggressive sales targets, the scope of the scandal disguised a troubling trend: Whistleblower claims are on the rise, and although companies fail at this all the time, there are ways to protect your bank from retaliation claims.

“I’ve seen many instances where something bad happens at an institution with an otherwise sterling reputation for doing the right thing. Something is uncovered at the institution. And then we see the follow-on claims of whistleblower retaliation,” says Kenneth Gage, a partner in the employment law practice of Paul Hastings and chair of its workplace retaliation and whistleblower defense practice.

Since the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and other regulators settled with Wells Fargo for $185 million last September, the media has been awash with reports about employees at the bank who claimed to have been fired or otherwise retaliated against for bringing the illicit sales practices to the attention of their supervisors, the human resources department, the bank’s ethics hotline, and even now-former CEO John Stumpf and the board of directors.

Wells Fargo has since investigated the whistleblower retaliation claims that originated from calls to its ethics hotline, concluding that the “majority of cases” were handled appropriately. But even if this proves to be the case for claims submitted through the other channels as well, the additional damage to Wells Fargo’s reputation has already been inflicted. Rightly or wrongly, the bank must now overcome the perception that it not only defrauded customers, but that it also punished employees who tried to stop their coworkers from doing so.

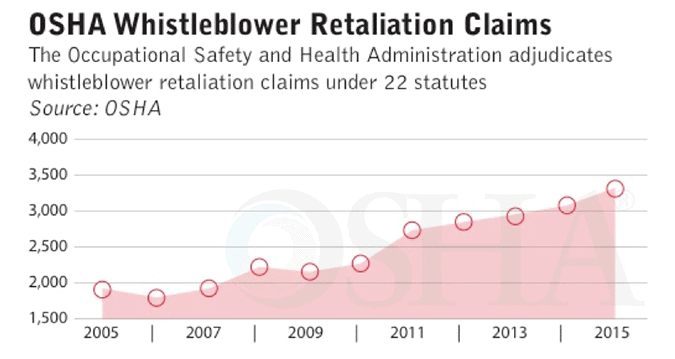

This sequence of events is by no means unique to Wells Fargo, which declined to comment for this story. The number of claims investigated by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA, which has jurisdiction over retaliation claims under 22 laws, increased 70 percent between 2005 and 2015. The same is true for whistleblower retaliation claims submitted to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission over violations of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which have risen 67 percent over the same stretch.

“The categories of protected activities under federal and state law have been expanding exponentially over the last ten years,” explains Bradley Cave, a partner and member of the management committee at Holland & Hart and former leader of the firm’s labor and employment practice. “Every new federal law seems to offer whistleblower protections.”

The Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 is a case in point. Title 10, known as the Consumer Financial Protection Act, protects whistleblowers who report violations of financial consumer protection laws. The number of such claims, which are investigated by OSHA, have increased from six in 2011 to 52 in 2016.

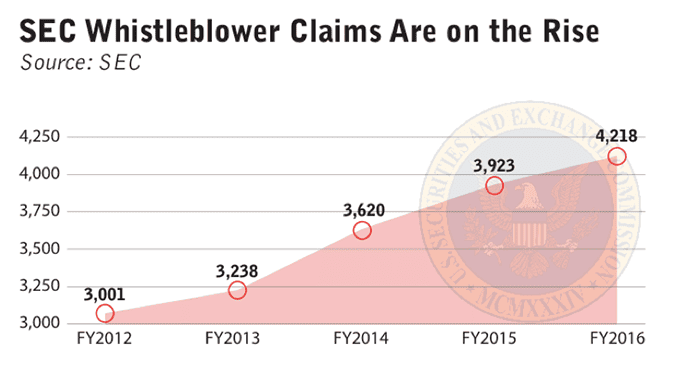

Dodd-Frank also directs the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to reward whistleblowers who provide information leading to successful enforcement actions. The SEC received 4,218 tips from whistleblowers in fiscal year 2016 alone, a 41 percent increase from 2012, and it paid out over $57 million in awards, more than in all previous years combined.

Defending against whistleblower retaliation claims is thus becoming a core component of any scandal. “Anytime a scandal occurs and it reduces the general level of trust in an institution, people who have had bad things happen to them start to wonder whether there’s a connection between the two things,” says Gage. “And the bigger the institution, the more easily people lose trust. It’s often inevitable that if you have a scandal, you’ll see follow-on claims of retaliation from people who feel that, for whatever reason, they tried to stop it.”

This isn’t to say that banks can’t minimize the incidence of whistleblower retaliation claims, because they can. The single most important way is to train frontline supervisors to identify potential whistleblower claims in the first place.

“In order for a whistleblower to be protected under most statutes, they have to be engaged in protected activity. That varies from statute to statute, but as a general rule, the standard is that a reasonable person in the employee’s position would have believed that something was going on in violation of the law,” says Gage. “It could be fraud. It could be discrimination. Whatever. But for their activity to be protected, they have to have a reasonable, good faith belief that the law is being violated.”

This seems straightforward, but it’s complicated by the fact that protected activity can arise in the course of an even informal conversation. “Most of the statutes don’t require the filing of anything formal,” says Cave. As a result, the people who receive complaints need to have a clear understanding of what types of things qualify as protected activity and what types of things are just personality disputes that can be managed without getting a third party involved, explains Gage.

Supervisors must also be trained to respond appropriately, particularly when the whistleblower has pre-existing performance issues. “Where I see these going sideways very often are situations where the person who’s raising the issues is already on shaky ground. It could be because of problems with their performance or that they’re not getting along with co-workers,” says Gage. “Then, all of a sudden, when they object to a particular practice that they believe to be illegal, their expression of concern is tainted by the perception that they’re a poor performer, and it’s not taken seriously.”

An unconstructive or dismissive response by a supervisor plants a “root of suspicion” on the part of the employee, says Cave. “Once that takes hold, it’s difficult to uproot. Any ongoing conflict even on separate topics between that manager and employee may be viewed by the employee as a retaliatory reaction.”

For the same reason, after a potential whistleblower has submitted a claim, there must be a “degree of separation” between the supervisor who fields it and the person tasked with investigating its merits. This is especially important in instances where the whistleblower is later subject to a poor performance review, demotion, termination or anything else that could be characterized as an adverse employment action. “At the end of the day, if a whistleblower brings a case and asserts a claim of retaliation, he or she still has to show causation. They still have to show that their protected activity and the adverse event are connected,” says Gage.

Finally, the most surefire way for a bank to minimize whistleblower retaliation claims is to promote a “culture of constructive dissent,” says James Dungan, a researcher at Boston College and the co-author of several studies on the psychology of whistleblowing. Dungan believes that by encouraging employees to engage in open and, if necessary, critical discussions about their workplace, those who observe organizational wrongdoing will be more inclined to air their grievances internally as opposed to taking them to the media or authorities.

Both Gage and Cave agree that avoiding retaliation claims is highly dependent on an employer’s culture. “If a company can persuade its employees that it is serious about affirming, and in some cases even rewarding, internal criticism of processes and decision-making, that will go great lengths in avoiding retaliation claims,” says Cave. “If you can make internal criticism a value of the company, an employee is less likely to think or claim that the company has retaliatory motives.”

Most importantly, says Cave, a bank can’t just say that it doesn’t condone retaliation, it has to back that up with action. “Every company has anti-retaliation policies. You have to be able to demonstrate that the company takes positive steps to encourage internal criticism and positive steps to explore, follow up on the criticism, make changes when warranted and reward employees who raise concerns when those concerns lead to positive changes in the company.”

Join OUr Community

Bank Director’s annual Bank Services Membership Program combines Bank Director’s extensive online library of director training materials, conferences, our quarterly publication, and access to FinXTech Connect.

Become a Member

Our commitment to those leaders who believe a strong board makes a strong bank never wavers.