Cybersecurity: What the Best Banks Do to Protect Themselves

The hack of JPMorgan Chase & Co. and other financial giants in 2014, which involved the theft of 80 million customer records, revealed an unfortunate reality in the age of the internet: Not even the largest institutions with their hordes of cybersecurity staff and big budgets are safe. “Even big institutions with the most robust cybersecurity procedures will find it tough to protect themselves from every threat. Cybersecurity is about risk mitigation, not risk elimination. There’s no silver bullet,” says Nicole Friedlander, the former head of the cybercrime unit for the U.S. Justice Department for the Southern District of New York, which prosecuted the JPMorgan hackers. She now works as special counsel for Sullivan & Cromwell LLP in New York.

Cybersecurity experts say the best banks have shifted away in the last few years from an assumption that they could keep the bad players out of their networks, and towards mounting a series of protective stances for when the inevitable occurs. “You will believe you can stop the breach from happening and you can’t,” says Dan Clark, the director of internal audit for Washington Trust Bank in Spokane, Washington, which has a little more than $5 billion in assets. Knowing that, the best banks follow certain practices to ensure good management of cybersecurity risks, while planning for the inevitable breach.

Risk Assessment

Many banks now are following the National Institute of Standards and Technology recommendations for cybersecurity and conducting a risk assessment to identify the bank’s greatest information technology (IT) risks. Regulators expect the board to oversee the bank’s IT security program, as detailed by the IT Handbook, published by the joint Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC). “You don’t want to hear [from management], ‘don’t worry about it, IT is taking care of it,”’ says Jeff Sacks, principal in the risk consulting group for Crowe Horwath LLP. As part of its oversight, board members commonly review dashboards showing the bank’s greatest risks, and a plan for how the staff will mitigate them. Regulators are increasingly asking banks about their progress on adopting the recommendations in the FFIEC’s cybersecurity assessment tool, which helps banks assess their risks, says Sacks. A good practice, and one not all banks do, is to assess the bank’s risks with penetration testing, where someone posing as a hacker tries to get inside the bank’s computer networks, to identify weaknesses in your employees’ security practices. That person might, for example, send to your employees phishing emails, which try to obtain personal information on your clients or your network passwords.

Ron Hulshizer, the managing director for the IT risk services group at the consulting firm BKD, does this sort of testing for banks all the time. He finds that 5 percent to 46 percent of bank employees will hand out their user names and passwords when asked through phishing attempts. “People are the weakest link,” he says.

Response Plan

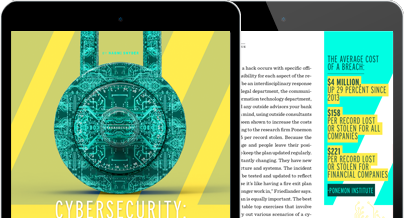

In addition to learning about management’s plan to mitigate cybersecurity risks, the best banks also have incident response plans in place before a hack occurs with specific officials assigned responsibility for each aspect of the response. There should be an interdisciplinary response team made up of the legal department, the communications team, the information technology department, human resources and any outside advisors your bank may need. But keep in mind, using outside consultants during a breach has been shown to increase the costs of the breach, according to the research firm Ponemon Institute, by about $5 per record stolen. Because the bank’s systems change and people leave their positions, it’s important to keep the plan updated regularly. “Companies are constantly changing. They have new employees, infrastructure and systems. The incident response plan has to be tested and updated to reflect that reality. Otherwise it’s like having a fire exit plan for a building you no longer work in,” Friedlander says.

Testing out the plan is equally important. The best banks walk through table top exercises that involve top managers who try out various scenarios of a cyberattack-for example, a major breach of customer records or denial-of-service attack where the bank’s website is down or even worse, says Chris Novak, director of investigative response for Verizon, which conducts such exercises as part of its consulting work. “The key is the executives need to be involved and understand how critical that is,” he says. “If the bank is down for a day, that’s huge.”

The reason such preparedness is important to the executive team is because cybersecurity is a business problem, not an IT problem, says Bryce Boland, the Asia Pacific chief technology officer for FireEye, a global security software provider. A massive breach will test the resources and skills of the upper levels of management and the board. “The threat to the business is huge,” Boland says.

The Ear of the Board

As a board member, if you don’t know who is in charge of your bank’s cybersecurity, then you don’t have someone who has the ear of the board, and Boland says that’s a problem. The board needs to ensure that the cybersecurity apparatus of the company has the resources it needs, and the board should have direct access to the person who heads up cybersecurity at the bank.

Banks that can afford it are increasingly designating a chief information security officer, or CISO, who does not report to the chief information officer, or the CIO, because the goals of cybersecurity often conflict with the goals of the bank’s information technology division. “It’s really critical to ensure that the security aspects are looked after by somebody who is not going to have a conflict of interest with IT,” Boland says. “The budget shouldn’t be dependent on what the IT people are doing.”

Developing the Board’s Knowledge

While the board should hear directly from the cybersecurity chief at the bank, the board shouldn’t rely on management alone to tell them everything they need to know, says Heith Rodman, an attorney for Jones Day. The board needs education sessions so it can develop its own understanding of the bank’s cybersecurity risks. One way to do that is for the independent directors to hire outside expertise to advise the board or the risk committee. “They should never have to go to management to beg for money to hire experts,” Rodman says. You could argue there is an inherent conflict of interest where management won’t want to tell the board about breaches or potential weaknesses in the bank’s infrastructure. Hiring outside experts is just another way to verify your bank is handling cybersecurity in the best way possible.

Bringing in outside expertise helps, but so does bringing people with cybersecurity expertise to serve on the board. It’s not easy to find people with such skills who also have the right credentials to serve on a bank board, but Columbus, Ohio’s Huntington Bancshares’ board did that last year when it recruited former deputy director of the National Security Agency Chris Inglis, who has advanced degrees in computer science and engineering. The board of Winston-Salem, North Carolina’s BB&T Corp. has K. David Boyer Jr., the chief executive of GlobalWatch Technologies, a security firm in Washington, D.C. Another avenue for increasing the board’s focus on cybersecurity is to start a subcommittee of the board that looks at technology risk, says Rodman. Board members also can talk to employees below top management to get a sense of whether the bank has the resources it needs or to further educate themselves about the bank’s security.

Board members are asking good questions and getting much more involved in cybersecurity than they were just five years ago, says Novak. Back then, it would have been rare for a corporate board to even hear about a sizeable cyber incident at the company. “Cybersecurity, for banks, is absolutely a board level issue and has been for a number of years,” Boland says.

The focus has changed, for boards and for the bank. Now, independent directors are paying attention and senior management-including those with responsibility for cybersecurity-are doing what they can to protect the bank even when a breach occurs, which has become increasingly difficult to prevent.

Join OUr Community

Bank Director’s annual Bank Services Membership Program combines Bank Director’s extensive online library of director training materials, conferences, our quarterly publication, and access to FinXTech Connect.

Become a Member

Our commitment to those leaders who believe a strong board makes a strong bank never wavers.