“The Biggest Threat to the Deposit Insurance Fund I’ve Ever Seen”

A little-known rule called the national rate cap is putting community banks in a bind.

A little-known rule called the national rate cap is putting community banks in a bind.

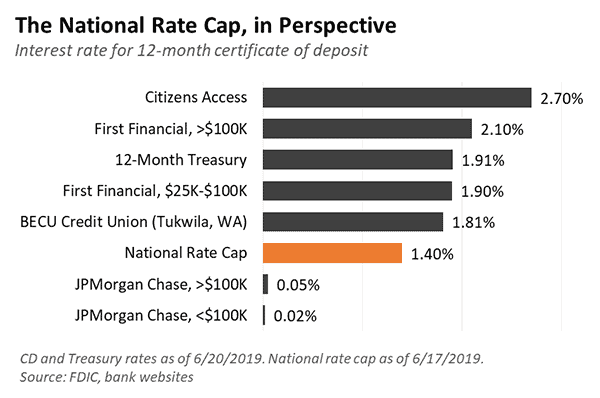

The cap tries to set a high-water mark for rates by calculating a weekly average of advertised interest rates for specific deposit products at branches, plus 75 basis points. This wasn’t a problem when interest rates were dropping or staying steady, but the higher rate environment has now inadvertently handicapped community banks as they compete for deposits.

Bankers say the rate cap, calculated and enforced by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., is unrealistically low compared to corresponding market rates. The difference could also make some banks appear riskier if examiners bring up deposit rates in exams.

Peoples Bank in Magnolia, Arkansas, uses wholesale funding to make loans for its low- to middle-income customers who lack deposits, says CEO Mary Fowler. The bank, which is well capitalized and has $200 million in assets, offers attractive rates to bring in and retain many of those funds.

The only problem? More than 90 percent of certificates of deposit (CDs) at Peoples Bank pay a rate that is higher than the rate cap.

“I call [these] traditional deposits, because they’re core as long as you’re paying the best rate in town. But we have to pay market rates for it,” she says.

Other banks are in a similar position, as higher rates have caused the national rate cap to lag the yield on Treasury securities of similar durations. This puts bankers like Fowler in a tough spot. They need to offer rates above the cap to attract or maintain deposits, but doing so invites skepticism from regulators. The FDIC declined to comment.

“Why would a customer get a CD from me when I can only hypothetically pay the national rate cap?” says Joseph Kiley III, president and CEO of Renton, Washington-based First Financial Northwest, a well-capitalized bank with $1.3 billion in assets. He points out that, at times, Treasuries paid more than 100 basis points above the rate cap.

Bankers say the cap also creates tension with examiners, who see it as a proxy for “potentially volatile” deposits. That’s because the rule, which should only apply to a small subset of thinly capitalized institutions, has become standard across the industry.

Examiners ask executives at healthy banks what they would do with these higher-rate deposits if the bank lost capital and was forced to abide by the cap, says John Popeo, a principal at the consultancy Gallatin Group. Popeo is a former FDIC regulator who helped resolve failed banks after the financial crisis, and represents institutions across the country that are well capitalized and do not have any immediate regulatory issues.

He says examiners are not threatening a regulatory downgrade but want to see how the bank would fund itself in the event it is no longer well capitalized. For some banks, the answer isn’t pretty.

The cap could lead to systemic problems if too many banks dip below well-capitalized levels during an economic downturn, as the FDIC prohibits less-than-well-capitalized banks from offering rates above the cap.

“When they pull your funding, you’re done,” Kiley says. “[Your bank is] just going to bleed to death.”

The FDIC has begun the process of changing the rate cap calculation, but Fowler worries that an economic downturn that threatens bank capital levels could come faster than regulators’ correction. She has been in banking for decades and says the rate cap is “the biggest threat to the deposit insurance fund I’ve ever seen.”

Executives from Peoples Bank wrote five comment letters on the request for proposal. Fowler points out that the FDIC calculated the cap using only Treasury yields prior to 2009, at which point it changed its approach.

In calculating the rate cap now, the FDIC uses an average of prevailing deposit rates at bank branches, but excludes credit unions, negotiated rates and special offers from the calculation. Using branches means that big banks are overrepresented, and online banks paying market-leading rates are underrepresented. Fowler says the FDIC should change this. She thinks it should compare the current approach to the old Treasury approach, and select the rate that’s higher.

Kiley questions whether a rate cap is an antiquated notion but hopes any change will account for how customers interact with banks and rate-shop in the digital age. If the rate cap continues to exist, he would prefer that the FDIC use wholesale funding rates from institutions like the Federal Home Loan Bank.

“We are living in a world where we pretend folks walk into branches and say ‘Hi’ to the teller … and wave to their money in the vault,” he says. “Everyone banks like they buy from Amazon.com. I don’t think there should be a rate cap.”