Cautious Optimism: Returns to Bank M&A

A group of nine industry experts were interviewed in two separate panel sessions, sponsored by Grant Thornton LLP, at the 2011 Acquire or Be Acquired conference. What follows is a synopsis of each participant’s thoughts on the future of bank M&A and what boards should be thinking about today.

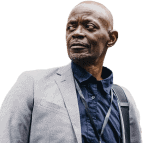

JOHN DUFFY

Chairman & CEO

Keefe, Bruyette & Woods Inc.

What is the outlook for normal deals and FDIC-assisted deals in 2011 and 2012?

I think we’re starting to see the early signs of increased traditional M&A activity. Clearly, the focus the last two years has been on FDIC-assisted deals. Most of the more notable bank failures have been resolved at this point, but there are still plenty of troubled banks to deal with, and I think it depends on size what your focus is. The larger banks are clearly going to focus on opportunities the size of Whitney Holding Co. and Marshall & Ilsley Corp., if they present themselves. The smaller banks couldn’t entertain buying a multi-billion dollar bank so a lot of them are still very focused on FDIC-assisted transactions. A lot depends not just on your size but also geography. If you’re located in Georgia or Florida you’re probably still focused on FDIC transactions because there were a lot of failed banks there. If you’re in Pennsylvania or someplace else where there weren’t a lot of failures, you’re probably looking at unassisted deals.

What are the principle factors that will drive M&A activity going forward?

I think one of the drivers of M&A is going to be the bank regulators, who are playing a role that they frankly haven’t played very much historically. I think they are being much more proactive in encouraging boards at troubled banks to find a total solution-that it may not just be a question of capital adequacy, but also a question of risk management, a question of management competency. I think they’re doing a fairly good job of scaring enough bank directors about their liability issues that in an indirect way, maybe the regulators are really one of the main drivers of M&A activity.

What is the outlook for asset quality in 2011 and its impact on deal volume and pricing?

We’re somewhat more optimistic about improved pricing and credit quality on the commercial real estate side as opposed to the residential side. There are still a lot of commercial real estate loans that are coming due either on bank balance sheets or in securitization pools. I believe the number for 2011 and 2012 is in excess of $500 billion of commercial real estate in both of those years for securitizations that are maturing, so there’s a lot to get through the pipeline. But banks know how to rework commercial real estate; it takes time and money. We’ve seen progress in 2010 and we expect to continue to see progress, assuming the economy continues to get a little bit better. On the residential side I think the outlook is much more uncertain given the amount of properties that are in foreclosure, the difficulties that buyers are having getting financing and the uncertain future of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. We’re less optimistic about any rebound in residential real estate, despite the kind of price depreciation that you’re seeing in places like Scottsdale, Arizona.

What are the most closely watched pricing metrics in today’s M&A market?

Buyers aren’t really looking at what they’re paying as a multiple of adjusted tangible book; they’re really looking at the earnings impact of the acquired institution because the factor that can be very significant is the projected cost saves. I think Comerica was willing to pay such a high price to acquire Sterling Bancorp, because Sterling had a 73 percent efficiency ratio, and without knowing what Comerica’s cost save assumptions were, I think they expect to make the deal accretive by the amount of cost saves that they expect to get. So I think the buyer looks at the earnings impact. And buyers also look at the impact on their capital ratios. If you’re going to do a deal, but will have to raise capital and create dilution for existing shareholders, that’s going to weigh on what price you’re willing to pay for that target.

How much consolidation do you expect to see among the country’s largest banks?

We look a lot more like Canada today than we did 20 years ago. I’m not sure exactly what percentage of the country’s banking assets the top four U.S. banks have, but it’s well north of 50 percent while the five largest Canadian banks have something like 90 percent of that country’s assets. So the industry is fairly concentrated, and consolidated at the top end. I think JPMorgan Chase may be the only one that has a substantial geographic hole that they would want to fill, and that’s the Southeast. So I don’t expect a lot of M&A activity among the top four U.S. banks. I certainly wouldn’t count on Bank of America doing anything because I think they are above the mandated ceiling on deposit market share. Below the top four there’ll clearly be M&A activity among those institutions. And who knows, the deposit caps could change. I think there’s more focus on the size of a bank’s total liability picture than on deposit concentration today from the regulatory point of view, because if you look at what got Iceland and Ireland in trouble, it was that those governments didn’t regulate the size of their banking industries and the banks basically brought down the countries.

GEORGE MARK

Partner

Grant Thornton LLP

What are the principle factors that will drive M&A activity going forward?

I have seen in several discussions and meetings with clients that there will be continued interest in M&A transactions during the next two years. However, part of the hesitation continues to be the regulatory landscape and its impact on banks. Banks are becoming more aware that landing a deal to strengthen and grow the company is crucial to staying in existence, and to potentially increase their capital and avoid tough situations in the future. There will also be continued difficulty in valuing these transactions given the uncertainty in credit marks in the company’s portfolio. It is crucial that companies that are interested in these transactions have the appropriate management in place to properly mark the portfolio to gain a true understanding of the worth of the potential acquired entity.

What do you see as primary post-merger integration risks today?

It is very, very costly from an integration standpoint to try and integrate a troubled institution, particularly in FDIC transactions because you need at least three sets of books, one from a regulatory perspective, one for GAAP and one for your accounting under SOP O3-3, which is the accounting pronouncement used in such acquisitions where you are acquiring loans with credit deterioration. As you value the portfolio, those credit marks are determined in a slightly different way than a traditional acquisition to the extent that you have to have certain inputs and various valuations using very sophisticated discounted cash flow models in these acquisitions. You will also need to evaluate and revalue this on a periodic basis. There are operational challenges, where acquirers will need to be quick to integrate the systems, records and operations of the acquired entity. Acquirers should have a dedicated and diverse team prepared to address issues that arise, from the moment they begin evaluating whether to bid all the way through the integration of the acquired institution.

How do potential deals impact a bank’s standing with regulators and shareholders?

On the one hand, these deals inspire confidence in the eyes of regulators and shareholders that the company is looking to grow and strengthen itself. However, increased scrutiny is a direct result of these transactions. In many cases, due to the fact that there is uncertainty surrounding these transactions, specifically the performance of the acquired portfolio, there is a higher level of risk that can be associated with such transactions. It is imperative that the company has the appropriate management in place to address questions and issues that arise.

What is the potential impact on a bank’s capital ratios and earnings in entering into an acquisition?

In many instances, FDIC-assisted transactions can result in significant day-one gains, which can have a large impact on earnings. However, whether that gain will be allowed to be counted, in whole or in part, toward the Tier 1 capital ratio by the FDIC and other bank regulators, can vary by transaction. The acquirer should discuss the capital impact with its primary banking regulator and accountants at the onset.

WILLIAM F. HICKEY

Principal

Sandler O’Neill + Partners LLP

Are we poised for an outbreak in M&A activity, and if so why?

I think we are. There is a significant number of banks out there that are undercapitalized and have credit issues, and the regulatory pressure right now is not going to let up, and the regulators quite frankly are really pushing these institutions towards a merger or sale. We talked with a $500 million bank recently that had a great regulatory exam a year ago. They just went through a regulatory exam and got hit with something they hadn’t heard about a year ago. It’s a little bit un-American, but unfortunately the regulators are going to really continue to push this consolidation.

How does the invisible hand of the regulator work behind the scenes to encourage M&A?

I don’t know whether their hand is invisible at all. It is very visible through the memorandums of understanding, and the cease and desist orders, and all the new requirements they’re imposing on all of the financial institutions. So legislating new capital ratios or legislating risk ratios would take too long, and they have the ultimate ability to dictate what the new ratios will be for individual situations. You can’t fight City Hall. It’s going to be very effective, as it has been.

Do you think M&A pricing levels may go back to where they were a few years ago?

I think we need to put our theoretical hat on, right? If the regulators are going to require more capital, capital ratios are going to go up, and within those capital ratios the predominant piece has to be common equity. Returns are down, leverage is down and earnings are down on a relative basis. So valuations fundamentally have to be down. When you think about the merger madness of 1998, when buyers’ stocks were trading at three times book and they could afford to pay two and a half times book-we’re a long way away from seeing the majority of banks trading north of two times tangible book in order to create those valuations.

Have most sellers adjusted downward their price expectations?

No, but I think they’re getting there. I think you have much more disciplined buyers that are not, at least in the short term, going to stretch for deals because of their own capital limitations, their own multiple limitations. So it’s going to take longer than we would all hope.

How much consolidation do you expect to see among the country’s largest banks?

I’d look at that a couple of different ways. How big do I have to be? Is it $100 billion? Is it $200 billion? I think now the 50th largest bank in the country is about $15 billion. So if I think I need to be $100 billion, that sort of gets me to where Fifth Third Bancorp or KeyCorp are now, and we know they want to get bigger. So you’re really going to have a huge bifurcated system. You’ll have the top 25 to 30 that will all be $100 billion and higher, and then another group $10 billion and very few under $1 billion.

What do you see as the primary characteristics of today’s M&A market?

I think we’re always going to have fully priced deals for franchises that have strategic value, where the only way someone can get into Boston or get into Texas is with one of the last remaining big franchises. Where I think the pressure is, is on the sellers. The sellers have to realize that it’s not about the price; it’s about the quality of the stock they get from the acquirer. What are its attributes? What’s the liquidity? What’s the growth potential and value? If I’m going to make the decision that I can’t compete given my size, then I want to get on the best, biggest, fastest boat that I can find to continue to grow my business. So the franchises that don’t have that strategic franchise value need to really make the hard decision of: “Alright, I know I’m not the most attractive girl at the dance, but I know that there’s a lot of people who want to dance with me, and I’ve just got find the right partner.”

If future investment returns are going to be down, will investors continue to buy bank stocks?

Very few investors in the long term are buying bank stocks because they have fabulous returns. They’re buying banks because they like the fundamental multiples at which they’re buying a dollar of earnings. So investors are going to recalibrate; they’re going to understand what the entry level needs to be in order to get their required returns, so I don’t think you’re going to chase bank stock investors out of the market because the returns are down. They’ll just require that they get in at levels that are lower. They’re not buying banks because they’re going to grow at 25 percent a year.

BEN PLOTKIN

Executive Vice President

Stifel, Nicolaus Weisel

What is the outlook for normal deals and FDIC-assisted deals in 2011 and 2012?

As companies start thinking about 2012 and growing their balance sheets, they’ll be looking for traditional M&A opportunities because the remaining FDIC problem cases are mostly very small banks. For that reason acquirers will revert back to traditional M&A as a line of business, especially since some of the barriers to healthy M&A activity that we’ve seen in the last two years-the lack of access to capital, the inability to market portfolios-will be diminished.

What are the principle factors that will drive M&A activity going forward?

I think it’s going to be comfort on credit. Acquirers have to be comfortable with their own portfolios and where they stand and they have to be comfortable on being able to value someone else’s portfolio.

Why are the boards at some troubled banks reluctant to sell out?

I think there’s this perception of an asymmetrical risk. Some boards don’t think there’s that much downside if they don’t sell, and if the economy improves they’re going to create a lot of shareholder value. That perception is about to change once the FDIC starts filing thousands of lawsuits against directors at failed banks and the publicity that that will create. I think the perception that there’s more upside than downside will change in the next 6 months.

Are there risks associated with waiting too long to sell?

We refer to it as the death spiral. If companies wait too long before they talk to one of us about raising capital or a sale, it’s too late, because at that point any acquirer or private equity firm is going to say they’d rather wait for an FDIC resolution than take the credit risk on their balance sheet. And we’ve seen it happen. I don’t know how many times we’ve all seen it in Florida and Georgia and other markets, where companies wait too long because they’re not assessing the risk appropriately and think it’s asymmetrical.

What is the outlook for asset quality in 2011 and its impact on deal volume and pricing?

I think asset quality is improving but given the unemployment problems the country faces, it’s going to be a long road back, because unemployment will be a long-range problem which means we’re going to have consumer credit problems for a while, and we’re going to continue to have deleveraging in the real estate markets, which means it’s going to be very hard for certain borrowers to refinance. I think we’re definitely in a post-crisis phase, but it’s just going to take a while until banks get back to 10-year averages in terms of non-performing assets.

How do sellers view valuations in the M&A market?

I’ve never known anyone to sell anything that they didn’t want more for, and part of our job as investment bankers is to close that expectation gap between sellers and buyers. I think there is a real awareness among potential sellers that M&A multiples are not going back to where they were historically and that’s an important leap in terms of knowledge for sellers. That doesn’t mean they accept doing deals at market-they still want more. But if we took a survey of the people here at the Acquire or Be Acquired conference, they would understand that they shouldn’t wait around for M&A multiples to go back where they were and that’s critical.

What’s the most important pricing benchmark today?

Sophisticated investors are going to do their own credit analysis, and determine what that might do to the book value of the target company. And then they’re going to look at the deposit premium relative to adjusted tangible equity. Now, that doesn’t mean that retail investors are focused on that; they’re still talking about the fact that Sterling Bancorp in Texas got over twice tangible book value. But I’d say that a student of the business is really focused on the relationship of the deposit premium to adjusted tangible equity.

How much consolidation do you expect to see among the country’s largest banks?

I think the forces of consolidation are present throughout the full spectrum of small community banks to large banks, but the level of deal activity is driven in large part by the strength of stock currencies, by valuations and by access to affordable capital. When you look at the top 50 banks, yeah, the forces of consolidation are there. However, I’m not so sure the valuations are there among many of the large banks’ stocks. If you look at some of our largest banks, they’re trading at lower multiples than some of our smaller banks. Once their valuations move up, I think you clearly will see M&A activity in that sector.

Do you expect the Dodd-Frank Act to be a catalyst that leads to increased M&A activity?

When a bank decides to sell, it’s usually not any one factor. In some cases, the incrementally higher compliance costs could be a tipping point. But for sellers, generally it’s the cumulative effect of thinking about their prospects for growth, and thinking about higher capital requirements and the macro economy, and then the prospect of higher compliance costs perhaps becomes a tipping point.

MICHAEL T. MAYES

Managing Director

Raymond James & Associates Inc.

Are we poised for an outbreak in M&A activity, and if so why?

I think what is really going to drive this next wave is a leveling off of the industry’s credit quality issues. A number of the more recent larger transactions, even for companies that have had significant loan problems, is evidence that buyers are starting to feel a little bit more comfortable now with getting their arms around asset quality problems.

How does the invisible hand of the regulator work behind the scenes to encourage M&A?

Given what the industry has been through, the regulatory scrutiny now is quite intense. Banks are coming out of their regulatory exams with a substantially higher level of classified loans than they expected, substantially higher capital requirements than they expected. For banks in certain size groups, raising that capital has been difficult, and that’s what causes a lot of them to really think about selling to somebody.

Do you think M&A pricing levels may go back to where they were a few years ago?

I think on some of the more recent transactions we’ve seen a little bit of lift in valuations compared to the very low valuations we saw before. But I also think that there will be reasonable constraint there going forward, because purchase accounting rules often force the buyer either to use more of its own capital to absorb the acquired bank, or go out and raise capital, and that will generally place a constraint on valuations getting too high. So I think there will be more M&A activity and valuations may move up a little bit from here, but not back to the levels we saw in 2005 and 2006.

Is it emotionally difficult for some boards to cash in their chips and sell out?

Most of the deals recently have been stock transactions, and I think there’s a growing appreciation for trading up to a more strongly valued stock as opposed to capitulating or cashing in your chips. Selling out for cash is one thing, and I think that’s a much more difficult decision. Exchanging shares and trading up into something where you feel the two companies can become more viable together is becoming a much more interesting strategy for boards. To a degree, it’s becoming inevitable. Whether it’s $500 million or $750 million or $1 billion, the fact of the matter is that the asset level necessary to survive is getting larger every year. And so companies that are, say, under $1 billion are much more sensitive now to having to rationalize the cost of doing business. And the idea of exchanging stock for stock, trading up, and having your organization live on in the next organization is becoming a little bit more interesting.

If that’s the strategy you decide to pursue as a seller, how do you find the right buyer?

I would say they come in all sizes, shapes and varieties. There’s probably a small group of companies that have been in contact with your bank over the months or years, and so there’s that one group of people where maybe the chemistry or the culture feels right. But there’s also another group that maybe you don’t know as well, but you admire from a distance. It might be a larger bank that’s in the market, and you like the way they do business, you like their financial fundamentals. It’s an educational process in board rooms where it’s nice on a regular basis to review who those companies are, to get comfortable with the nature of their business and how that fits with yours, and from time to time get together on a social basis just to get to know each other and to see if there is some chemistry there. So it comes from all different avenues, but I think the best way to do it is for the board to be proactive in identifying who those companies might be, and also being proactive in terms of developing some relationships.

I think what also happens sometimes is boards end up evaluating two or three different options at the same time. One of them may be selling, one of them may be a merger of equals, one of them may be raising some capital, and one of them may be buying a bank. What happens is the options start funneling down to something based on what they’re hearing back in each of those scenarios. So I think there’s a little bit of reluctance to say let’s choose one until they really know what the outcomes of all these other options might be.

How much consolidation do you expect to see among the country’s largest banks?

I think one thing that’s going to happen is the top 50 banks might consolidate into a number that’s about half that, but banks below $10 billion or even below $1 billion will consolidate as well. It’s almost like we have two different groups consolidating. As the industry bifurcates more, it’s almost like each segment is consolidating within itself, as opposed to smaller banks getting pulled up into a bigger category.

What do you see as the primary characteristics of today’s M&A market?

I think from the seller’s point of view, scarcity value is important. Franchise value is important. Having your arms around your credit quality issues is important. And those things are all coming together right now. There are franchises out there that are the last best thing available if you want to get into a certain market. So that creates some real strategic value. From the buyer’s point of view, I think what’s changed is buyers are clearly picking and choosing their spots much more carefully, they’re much more disciplined and they’re much more concerned about the impact of an acquisition on their own share price and also very concerned about the impact of an acquisition on their capital. So I think from the buyer’s point of view you’re going to see a more disciplined buyer and a more limited number of buyers.

STEPHEN M. KLEIN

Partner

Graham & Dunn P.C.

Are we poised for an outbreak in M&A activity, and if so why?

I think there will be a tidal wave of acquisitions because to get to 5,000 banks in the U.S., we basically have to have 300 to 400 deals a year over the next decade and I think that will happen. But I also think credit quality is the critical element. When everybody gets comfortable with that and they feel we’ve bottomed out on real estate values, I think regulators and buyers will feel more comfortable. There are two other things to consider. A lot of potential buyers have raised a lot of capital in the last few years, and they’ve gotten away with that because it’s perceived as a sign of strength, but at some point, the market’s going to demand a return on that capital, and those banks are going to feel compelled to merge. We also can’t overlook the fatigue factor. Boards and management teams are really tired and aging, and their 10-year plan to grow and sell didn’t work, and they want an exit strategy. They’re willing to take less because they want to get out. Shareholders also are tired of waiting. I think this year will be a year of transition. Maybe in 2012 the tidal wave will start.

How does the invisible hand of the regulator work behind the scenes to encourage M&A?

The regulatory driver is capital. There’s a middle pack of banks that can’t access the type of capital they need-we’re talking about maybe $20 million dollars or more-because that’s too small an amount to interest the larger investors. So they’re really shut out and the regulators will not let them earn their way through their problems-they’re going to force them to raise the capital. And if they can’t raise the capital, they’ve got to merge. If you’re less than $1 billion, the regulators are going to squeeze you out. I’ve seen statistics that 80 percent of the troubled banks are under $500 million, or something like that. And that’s what the regulators are going to do; they’re going to shrink those banks out of existence. But the $1 billion banks that have much more of an impact on the system and the deposit insurance fund, I think they’ve shown a tolerance for them.

Have most sellers adjusted downward their price expectations?

You’ve got to ask yourself where your bank is going to be in three years. Even if you survive this turmoil and you can hang in there, are you going to be able to add more value for your shareholders? Other than stabilizing asset quality, are you going to have any earnings to sell and are takeover premiums going to be higher? If you wait three years, you may not be any better position. A lot of people are coming to that realization and I think that will force boards and management to be more realistic about doing deals now.

What changes do you expect to see in the M&A market?

I think we’ll see creative deal making, where the acquirer pays some money upfront and then a payout over time tied to the performance of the seller’s loan portfolio, rather than getting into a debate over how those assets are going to perform. Let’s see how it plays out over a three-year period. If it does well, the shareholders get something. If it doesn’t, the buyer has been protected. That could remove an obstacle to doing deals, and make the regulators more comfortable because the risk is taken away from the buyer, which I think the regulators are concerned about. We haven’t seen as many of those deals as we should, and I think that’s a way of accelerating the process.

MIKE MCCLINTOCK

Managing Director

FBR Capital Markets

What is the outlook for normal deals and FDIC-assisted deals in 2011 and 2012?

We think asset quality is really improving across the industry and that’s going to trigger more activity. Buyers are more comfortable with their credit quality and they’re more comfortable with their targets’ credit quality. As far as FDIC deals are concerned, there are very few large banks still available unless the government changes its philosophy on seizure, so most of that activity will be in Illinois, Florida and Georgia, involving banks with less than $1 billion in assets. That’s what we think.

What are the principle factors that will drive M&A activity going forward?

I actually think the government is going to take a strong hand in driving merger activity. We’ve had a couple of clients that received the same CAMELS rating they did in prior exams only to have someone in Washington overrule and require further write downs in the assets, triggering a significant change in the CAMELS rating. That, of course, has forced the board to make some decisions about capital raising and the bank’s strategic plan, which they heretofore hadn’t thought of. So I really think the regulators are going to be much tougher.

What is the outlook for asset quality in 2011 and its impact on deal volume and pricing?

We think asset quality is getting better. We still don’t think the banks are going to be dumping assets at the prices that are currently being offered, but with asset quality improving, and their provisioning for loan losses diminishing, they’re going to try to earn their way out of their problems.

Are most banks more willing to do deals than they were two years ago?

First, the buyers have to be comfortable with their own balance sheets, and when they’re comfortable that they have their hands around the risk in their loan portfolios, whether it’s commercial or residential or C&I, then they’re going to be willing to look at somebody else’s. But until they’re sure about their own credit risk, they’re not going to buy somebody else’s problems if they’re not sure what their own are.

What do you see as primary post-merger integration risks today?

There’s a lot less discussion about social issues today than there was five years ago, and a lot more discussion of who the good lending officers are, who the good loan collectors are, and who came up with that write off and was it appropriate. So if there’s integration risk it’s making sure that your people and their people are looking at the assets in the same way and in a realistic way so that you don’t underestimate the potential problems.

How much consolidation do you expect to see among the country’s largest banks?

I think it’s going to be very hard for the four largest banks to get any bigger. The industry is largely consolidated because if you took the next eight largest banks, they don’t add up to the fourth largest bank in terms of size. So at the very top end of the pyramid I don’t think there’s going to be a ton of change, but below that there’s a lot of consolidation still likely to happen.

Do you expect the Dodd-Frank Act to be a catalyst that leads to increased M&A activity?

I think that only for the smallest banks could it possibly be an issue because they don’t have the staff to manage the compliance burden, although some of that can probably be outsourced. But I think the tipping point for banks in terms of selling out is really the asset quality issue. If those don’t get resolved I think the regulators will be pushing and I think then the board will have a decision to make. “Our stock’s not going to go anywhere for three years so why don’t we take someone else’s?”

RONALD H. JANIS

Esq. Partner

Day Pitney LLP

What is the outlook for normal deals and FDIC assisted deals in 2011 and 2012?

We’ve seen a lack of interest as compared to a year and a half ago in FDIC deals and it looks to me from the bidding results that people, other than private equity groups, are not that interested. We’ve certainly seen an increase in the interest and thought being given to traditional M&A deals, although the accounting rules will force acquirers to give more thought and contemplation to the necessity of raising additional capital. None of the community banks like the dilution that comes with raising capital, and I don’t think the smaller banks have thought through what they need to do to get deals accomplished when the target is substantially larger than the acquirer.

Why are the boards at some troubled banks reluctant to sell out?

I think boards understand the risk, but when they don’t see much of a difference between selling out and not selling, if all they’re going to get is 50 cents a share, they’re really not motivated sellers, even though it would be better to get 50 cents a share than let the whole thing go down. Part of it is just psychology. Some of them don’t believe that they’re facing the problems that they’re facing until it’s way too late, and I think sometimes they’ve chased dreams for too long. My advice to them is, you have to be realistic about it and listen to your advisers under certain circumstances, but it’s hard to get them over the dream and the fantasy.

Do you expect the Dodd-Frank Act to be a catalyst that leads to increased M&A activity?

Dodd-Frank obviously is going to have compliance costs associated with it but from the perspective of what has really driven compliance costs up, I think the AML/BSA issue has affected so many banks, added so much expense, and made things so complicated that while the addition of Dodd-Frank will be difficult, you will have trade groups helping the educational process and spreading the cost. So I don’t know that Dodd-Frank itself will raise the cost significantly enough for community banks to make a sale necessary.

JEAN-LUC SERVAT

Managing Director

RBC Capital Markets

Are we poised for an outbreak in M&A activity, and if so why?

The main driver of M&A is regulatory pressure and capital needs. One of the main drivers in the top 50-and that’s probably a separate group-is the necessity to get revenue growth. In a deleveraged environment, generating decent loan growth and earnings that are going to satisfy the investors that have put up probably $500 billion dollars worth of capital is a big challenge. For the top 50 bank holding companies, being able to generate top line growth or EPS growth is really the driver. Back in the ’90s it got to the point where we were doing 400 to 500 deals a year. All of us were probably just starry eyed. Of course, we didn’t have to contend with purchase accounting like we do today, so I don’t think we’ll get quite to that level of activity.

How does the invisible hand of the regulator work behind the scenes to encourage M&A?

I think the regulators have been remarkably slow. The regulatory forbearance that has been in effect has led many of our clients to think that things are OK: “You know, they haven’t come to me yet. They might have taken the guy next door, but I’m OK.” It’s not until they actually go out and proactively seek permission to repay TARP out of earnings or consider an acquisition plan that they all of a sudden get the wake-up call from the regulators that, “Huh-uh, you’re not ready to do that.” But that doesn’t happen often enough, and one of our big fears will be that with an election year coming up in 2012, the regulators might continue these practices which have served them well, but unfortunately leave a lot of people with the notion that they’re OK. It sounds very self serving from an investment banking standpoint, but I do think that that has been an issue.

Have most sellers adjusted downward their price expectations?

I don’t think most companies have a good sense of what number to get. You inevitably have one board member that’s fixated on the last decade and is out there with his or her expectation of getting three times book. Or you’ve got people who have been beaten back so badly that they practically take anything to get out. None of the numbers are reliable yet. We don’t have a lot of metrics that they can hang their hat on. So it’s a tough one. I think they’re all still going through a discovery process.

If a board decides to sell the bank, how should they go about finding the right buyer?

I think people generally have a pretty good idea, or at least over time develop a good idea, whom they would sell to. But I don’t think companies proactively make a clear decision to sell. They sort of slip into it. A lot of people tend to play a little game of responding to interest and sending us out to ferret out interest and then responding to the process. I think no CEO or board ever really wants to be viewed as having made a categorical decision to end their lives as such and move on. They get there, but they get there in a circuitous way through a back and forth game, so that they know when they really put themselves up for sale that they’ve got the parties lined up or one party lined up.

How much consolidation do you expect to see among the country’s largest banks?

I bet in the next three years that the top 50 turn into 25 or 26. I think there are a lot of institutional investors who remember when bank stocks used to trade at 20 times earnings but are now being told that price-earnings ratios will probably be somewhere between eight and 11. A very large bank doesn’t have a lot of options to change the economics, and M&A is clearly the only way you’re going to be able to enhance revenues and increase those returns. So I think investors are putting pressure on management teams to perform. |BD|

Join OUr Community

Bank Director’s annual Bank Services Membership Program combines Bank Director’s extensive online library of director training materials, conferences, our quarterly publication, and access to FinXTech Connect.

Become a Member

Our commitment to those leaders who believe a strong board makes a strong bank never wavers.