The Emerging Impacts of Covid Stimulus on Bank Balance Sheets

Brought to you by OTC Markets Group

In the middle of 2020, while some consumers were stockpiling essentials like water and hand sanitizer, many businesses were shoring up their cash reserves. Companies across the country were scrambling to build their war chests by cutting back on expenses, drawing from lines of credit and tapping into the Small Business Administration’s massive new Paycheck Protection Program credit facility.

The prevailing wisdom at the time was that the Covid-19 pandemic was going to be a long and painful journey, and that businesses would need cash in order to remain solvent and survive. Though this was true for some firms, 2020 was a year of record growth and profitability for many others. Further, as the SBA began forgiving PPP loans in 2021, many companies experienced a financial windfall. The result for community banks, though, has been a surplus of deposits on their balance sheets that bankers are struggling to deploy.

This issue is exacerbated by a decrease in loan demand. Prior to the pandemic, community banks could generally count on loan growth keeping up with deposit growth; for many banks, deposits were historically the primary bottleneck to their loan production. At the start of 2020, deposit growth began to rapidly outpace loans. By the second quarter of 2021, loan levels were nearly stagnant compared to the same quarter last year.

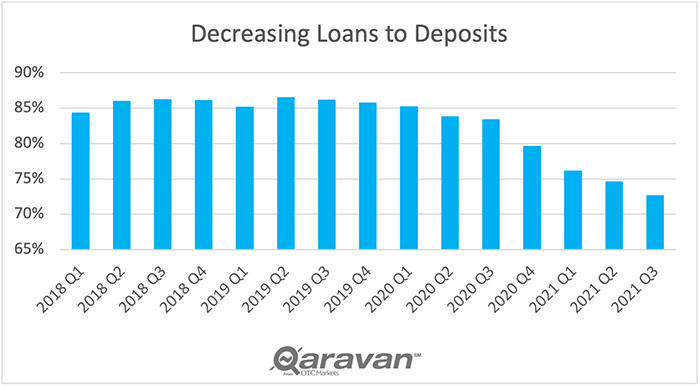

Another way to think about this dynamic is through the lens of loan-to-deposit (LTD) ratios. The sector historically maintained LTDs in the mid-1980s, but has recently seen a highly unusual dip under 75%.

While these LTDs are reassuring for regulators from a safety and soundness perspective, underpinning the increased liquidity at banks, they also present a challenge. If bankers can’t deploy these deposits into interest-generating loans, what other options exist to offset their cost of funds?

The unfortunate reality for banks is that most of these new deposits came in the form of demand accounts, which require such a high degree of liquidity that they can’t be invested for any meaningful level of yield. And, if these asset and liability challenges weren’t enough, this surge in demand deposits effectively replaced a stalled demand for more desirable timed deposits.

Banks have approached these challenges from both sides of the balance sheet. On the asset side, it is not surprising that banks have been stuck parking an increasing portion of the sector’s investment assets in low-yield interest-bearing bank accounts.

On the liabilities side, community banks that are flush with cash have prudently trimmed their more expensive sources of funds, including reducing Federal Home Loan Banks short-term borrowings by 53%. This also may be partially attributable to the unusual housing market of high prices and low volumes that stemmed from the pandemic.

As the pandemic subsides and SBA origination fees become a thing of the past, shareholders will be looking for interest income to rebound, while regulators keep a close eye on risk profiles at an institutional level. Though it’s too soon to know how this will all shake out, it’s encouraging to remember that we’re largely looking at a profile of conservative community banks. For every Treasury department at a mega bank that is aggressively chasing yield, there are hundreds of community bank CEOs that are strategically addressing these challenges with their boards as rational and responsible fiduciaries.

Visit https://www.otcmarkets.com/market-data/qaravan-bank-data to learn more about how Qaravan can help banks understand their balance sheets relative to peers and benchmarks.