Banks Brace for Exploding SBA Loan Demand

It’s hard to run a small business in the best

of times. Right now, it’s all but impossible.

“It took me 11 years to get comfortable and

make enough money to create a cushion so I didn’t have to worry if the pub had

a slow period,” wrote Natasha Hendrix in a recent Facebook post. Hendrix owns

McCreary’s Irish Pub & Eatery in Franklin, Tennessee; she’s also my

sister-in-law. Business was doing so well that she closed the restaurant to

remodel its bathrooms in advance of St. Patrick’s Day – the Super Bowl for

Irish pubs.

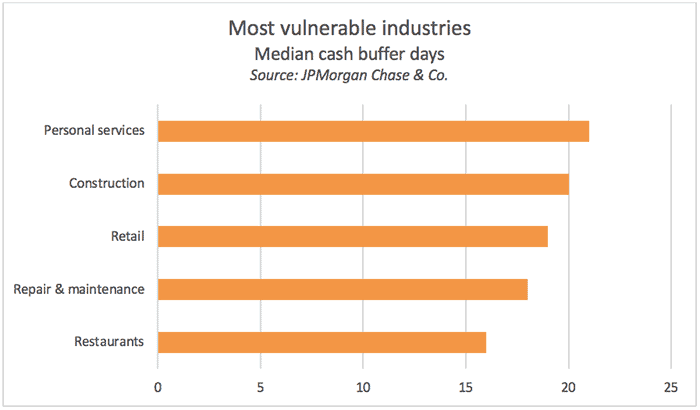

The complete evaporation of revenue for a

small business like McCreary’s is mind-boggling. In 2016, a JPMorgan Chase

& Co. study found that the median small business can survive without cash

flow for a little less than a month; a quarter of them can make it just two

weeks.

Small business owners are left questioning whether they can survive this severe and sudden downturn. “Everyone in this position has to START OVER. Build again,” wrote Hendrix. “Sure, people CAN do it but the real question I have for myself is … do I WANT to?”

“It’s a time for banks to be heroes,” said

Curt Queyrouze, CEO of $827 million TAB Bank Holdings, during a recent digital

conference hosted by MX.

A number of banks have announced deferrals on

loan payments and are offering additional loans; Queyrouze tells me loan growth

for term loans to small and mid-sized businesses had already tripled by late

March at Ogden, Utah-based TAB, mostly to bridge expenses to weather the crisis.

But a lot of the relief – up to $349 billion – promises to come through the “Paycheck Protection Program.” This is a special Small Business Administration loan, similar in concept to an emergency loan bad credit guaranteed approval, created through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act.

Small businesses can access PPP loans through existing SBA lenders and other participating financial institutions effective April 3; independent contractors and self-employed people can take advantage of the program beginning April 10. The terms are the same for all borrowers – two-year terms at 0.5% interest – and loan payments are deferred for six months. Use of the loans are restricted to payroll costs, including benefits; rent or interest on mortgage obligations; and utilities. The U.S. Treasury has supplied an information sheet for borrowers. (In a late press conference on April 2, Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin announced the interest rate on these loans would be raised, to a still-low 1%. The SBA then released an interim final rule with more information.)

Demand promises to be strong for these new SBA loans – many small businesses need cash now. But implementation is proving to be a challenge, and there’s a limited amount of time for small businesses to apply; June 30 is the deadline for the PPP loans. Additionally, there’s concern that the $349 billion in available funds won’t be enough.

At $239 million Farmers State Bank, Small Business Lending President Chris Healy has put in long hours to stay abreast of these changes and get information out to the small businesses in his markets, using email marketing, the bank’s website and videos on its social media channels.

The bank, based in Alto Pass, Illinois, is

already an SBA lender and is familiar with the intricacies of the agency’s

process. It has also shifted its technology to prioritize these new loans. The

process has been iterative, with Healy uploading and sharing new requirements

with customers as information provided by the SBA and Treasury evolves. The

entire process is digital; Farmers was able to pivot quickly because it already

had the technology in place.

Healy tells me roughly 300 small business

customers started applications before

April 3. That’s 12 times the volume in a normal year – the bank typically closes

around 25 SBA loans. However, some worry the industry won’t be able to meet

this influx of demand.

In a statement released April 2, the Independent Community Bankers of America cited key barriers for financial institutions. The low interest rate means banks won’t be able to break even on the loans, the two-year terms are incredibly short, and the guidelines are restrictive.

The low interest rate and abbreviated term

could limit the availability of these loans, said Chris Hurn, the CEO of Lake

Mary, Florida-based Fountainhead Commercial Capital, a nonbank commercial

lender, in a recent webinar. Secondary markets won’t be interested in

purchasing the loans. The U.S. Treasury has indicated it will purchase them,

but a mechanism for doing so hasn’t been made clear.

“We’re still awaiting the final rules of how

to do this, but being an experienced SBA lender already, we’re familiar with

following their intricate procedures and guidelines and so forth, and this is

going to be a significantly stripped-down version of that,” Healy says. However,

“the Treasury did shock us … with laying out the terms on the two-year basis

and a 0.5% interest [rate].”

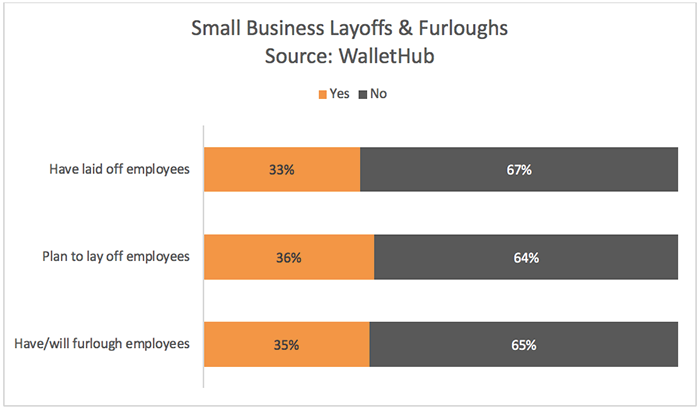

A key provision for small businesses is that these loans can be forgiven under certain conditions: if the proceeds are used as required, and employee and compensation levels are maintained over the eight-week period after the loan is made. The intent is to ensure Americans still have jobs after nearly 10 million have filed for unemployment in the past two weeks alone. (Small businesses employ 47% of working Americans, according to the SBA.)

However, guidance is needed on the

documentation and calculations that will be required to determine loan

forgiveness, said Hurn.

But without the new SBA program, Healy says Farmers wouldn’t be able to support small businesses to the degree necessitated by the crisis. He expects the government to ultimately buy these loans back. “If we do a $5 million loan to help a small business, that’s a big loan for us but we can sell it back to SBA immediately, and they’ll buy it from us at the principal value of the loan,” says Healy.

Small businesses need relief. Long after this crisis has passed, those that survive will remember how banks helped them through it.