Jackie Stewart is the Executive Editor of Bank Director. She is responsible for writing and editing features for the company’s weekly newsletter and quarterly print magazine and oversees sponsored research reports. Jackie is particularly interested in community banking and M&A activity. She previously served in a number of reporter and editor roles with American Banker, including executive editor of American Banker Magazine. She has also covered retirement issues for Kiplinger and spent two years teaching middle school literacy in the Bronx, New York, through Teach For America.

Why “Mattering” Matters to Nicolet’s CEO

*This feature is part of the 2025 RankingBanking report.

There has been much discussion within the financial services industry about what banks need to do today to thrive or even survive. But to Mike Daniels, CEO and chairman of Nicolet Bankshares in Green Bay, Wisconsin, this boils down to one word: Mattering.

“I say this to the investment analysts. They want to talk about [net interest margin] and [basis points] and the financials, but how do you engineer that?” he asks. “Our premise has always been simple. If we can matter to our customers, matter to the communities in which we operate and matter to one another, we can create an environment of shared success. We can provide exceptional shareholder returns.”

There were more than 4,000 banks in the U.S. at the end of the first quarter, according to data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Of those, more than 150 were based in Wisconsin. There are several thousand more credit unions and an ever-growing list of fintechs that are providing banking services.

Given this breadth of choice, how does any bank in the U.S. make itself matter? At Nicolet, the answer is a culture that revolves around ensuring that customers, shareholders and employees all thrive, and it means striving to serve all of a customer’s needs.

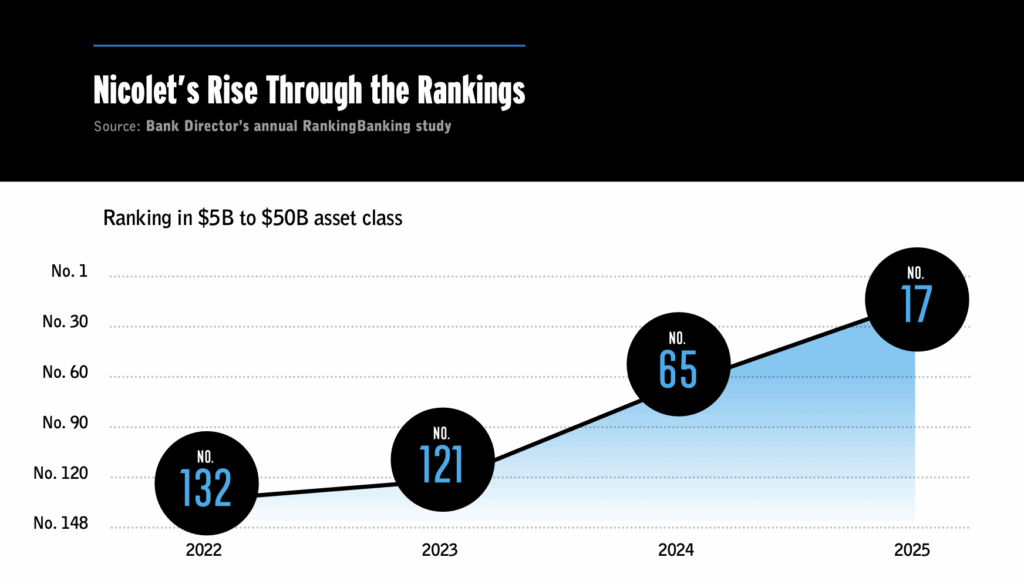

It seems as if the bank’s strategy is working. This year, the $9 billion Nicolet ranked 17th in Bank Director’s RankingBanking list for institutions with between $5 billion and $50 billion in assets, based on full-year 2024 results. That’s a jump from coming in at No. 65 in 2024, No. 121 in 2023 and No. 132 in 2022.

“There’s no doubt it is one of the higher performing banks across our Midwest coverage,” says Damon DelMonte, a managing director of equity research at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. “They have built a strong earnings engine. … Their approach to how they run the bank and their execution on their strategy has led to attractive returns. It’s a high quality company with great management, and that shines through in the results every quarter.”

Capturing a Full Relationship

Nicolet is primarily focused on originating commercial and industrial loans, a business line that lends itself well to “mattering” to its customers. That’s because this type of lending generally involves developing a deeper and ongoing relationship with the borrower that includes providing them with other products, such as treasury management services or a business savings account.

At Nicolet, this even extends to striving to provide retirement plan services for a company’s employees and wealth management for the owners. “A lot of the time we know that people are going to be wealthy before they know they are going to be wealthy, because they are grinding it out every day and they don’t realize what they just built,” Daniels says of Nicolet’s wealth management business.

Nicolet’s core return on average assets was 1.5% at the end of 2024, which ranked 22nd out of 150 banks with between $5 billion and $50 billion in assets, according to the RankingBanking analysis. That points to its success with building relationships.

C&I can also mean greater stability for a bank since it’s a heavier lift for a customer to move his or her business to another institution. “With commercial and industrial lending, you are establishing a real sticky relationship with that particular borrower,” says Joel Pruis, a senior director in the commercial and small business segments at the consulting firm Cornerstone Advisors. “To switch banks, it is very challenging for the customer.”

There are also greater opportunities for fee income revenue streams. Nicolet earned roughly $82 million in noninterest income in 2024, more than double the prior year, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence. In contrast, CRE loans are largely transactional, meaning the borrowers are simply looking for the best interest rate they can get. About 22% of Nicolet’s portfolio are CRE loans, and even in those cases, the bank normally has a deeper relationship with the borrower, Daniels says.

Daniels’ office is on the third floor of Nicolet’s headquarters in downtown Green Bay. It is across the Fox River from the Neville Public Museum of Brown County, a local nonprofit that has two dinosaurs made from recycled metal wearing party hats outside its doors. “If something hits the street, like this apartment building going up across the street or those apartment buildings there,” Daniels says one day in May while gesturing out of his window to construction projects near the Neville and its celebratory dinosaurs, “all they’re looking for is the lowest rate.”

If a developer does reach out to Nicolet about a potential loan, they often don’t like the terms, Daniels says. The bank requires the borrower to put in significant cash as equity and offers shorter terms than other lenders. These conditions are usually unattractive to the developer, and they end up taking their project elsewhere. “That’s not business. That’s just booking assets to book assets,” Daniels says.

C&I is often seen as riskier than CRE lending. In terms of charge-off rates, CRE loans fare better than commercial loans, Pruis says, though he notes that’s a “myopic view” of these different business models since it doesn’t take into account the better yields and other revenue streams that C&I credits garner. “If you’re heavy into C&I, then the net impact is you get better pricing to compensate for the higher charge-offs,” he adds. “The net performance is overall better.”

Daniels believes that C&I has its own advantages when it comes to risk management. If this type of business begins to struggle, the owner has more levers to pull to right the ship, such as cutting costs or increasing prices. “You can do a lot to fix an operating company,” he adds. In contrast, “there’s only one way to fix a bad CRE loan, and that’s to write it down and sell it.”

Still, much of this strategy depends on Nicolet gaining a significant share of a customer’s wallet. To achieve this, no one is referred to as lenders, and instead employees are considered bankers, Daniels says. No one sees their job as merely originating a loan; their jobs are in relationship development, he adds.

Compensation is not based on commission for originating loans. Employees are paid first based on how the company overall performs and then their individual contributions second. That ensures monetary incentives align with this philosophy. “If you turn them into portfolio managers, they quit producing,” Daniels adds.

Emphasizing how personal these financial decisions can be for customers and borrowers is also part of the bank’s culture. Recognizing and understanding this is essential to developing these deeper relationships and convincing customers Nicolet is a partner to them. Daniels notes that during a recent meeting with Nicolet’s mortgage bankers, he told the group that he never wants to hear them say their work isn’t personal because that simply isn’t true. Daniels, who is known for his bluntness, used more colorful language to get his point across.

“When people come to see you to buy a house, it might be the biggest investment they’ve ever made in their life. That is intensely personal to them,” he adds, “as is buying a business and putting your life’s savings and everything on the line trying to build something. We have to take the approach that, if you want to build that relationship, they have to understand that it’s personal and it matters. How can we help you make your life’s work into something and then help you plan for the transition, for the sale, for the succession, wherever you are in your lifecycle?”

More Than Smoke and Mirrors

This year is the 25th anniversary of Nicolet’s founding and over the last quarter of a century, the bank has completed nine bank acquisitions and continues to look for more deals. It now has more than 50 branches across four states, though it has steered clear of Wisconsin’s largest markets, Milwaukee and Madison, where the bank’s presence would likely only draw an indifferent shrug from potential customers. “Why would you go someplace where nobody cares that you’re there when you can do so many good things where you matter,” Daniels says.

This demonstrates Nicolet’s culture of wanting to “lead local” and plays into their business model of wanting to gain a significant share of customer wallet, DelMonte says. “If you are a less established bank in a market and you are trying to cross sell other products to them, then there might be more reluctance,” he adds. “But the relationship that Nicolet has is that people want to work with them. That allows them to tap into other products and services.”

Nicolet is certainly an integral part of its hometown of Green Bay. The company is a partner to the Resch Center, a local arena that hosts everything from minor league hockey games to Monster Jam events. The venue is across the street from Lambeau Field, home of the beloved Green Bay Packers, where Daniels serves on the board. And in a nod to the state’s dairy industry, during one week in June, a live cow was sitting under a tent in a Nicolet branch parking lot.

“You can walk around the community and look at a map of significant businesses that were not here prior to Nicolet’s founding, businesses that would either be very small or non-existent if it wasn’t for [Daniels] and [co-founder Bob Atwell’s] formation of the bank and willingness to make bets on businesses,” says John Dykema, Nicolet’s lead director and a local business owner.

Daniels and Atwell started Nicolet in 2000, with Daniels cheekily calling the founding of the bank “Mike and Bob’s Excellent Banking Adventure,” a reference to the 1989 film “Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure” about two high school friends traveling in time.

The pair had worked together as commercial bankers at the now $43 billion Associated Banc-Corp, a regional institution also based in Green Bay, before deciding to strike it out on their own.

They believed “there was an extraordinary opportunity in our area [northeast Wisconsin] for a highly focused community bank,” according to the bank’s first annual report. The name Nicolet comes from Jean Nicolet, the French explorer who is considered the first European to have traveled through what is called Wisconsin today.

Nicolet follows a “three circles” vision, which centers around the idea that customers, employees and shareholders all have their own separate interests but that it’s the company’s job to create shared success among the groups. This philosophy is then driven by the bank’s core values: “Be Real. Be Responsive. Be Personal. Be Memorable. Be Entrepreneurial.” Daniels has these core values — totaling just 10 words — hanging from the ceiling in his office as a piece of artwork of sorts.

It’s certainly not unusual for a bank to have a corporate mission statement or vision that supposedly drives decision-making and operations. But Nicolet seems to truly embrace it. Terry McEvoy, a managing director and research analyst who follows the company for Stephens, notes that the bank’s financial performance over the years demonstrates that this type of discussion “is not just smoke and mirrors.”

In fact, during McEvoy’s first-ever meeting with Nicolet, the management team kicked off the discussion by outlining this three circles philosophy. “It’s more than just corporate speak to them. It is a mission that goes back to day one, and they continue to live by it today,” he says.

The company’s stock price has increased by almost 300% since Nicolet’s stock moved from being traded over the counter to being listed on the Nasdaq in 2016. That beats the KBW Nasdaq bank stock index by a significant margin over that time period. “Their stock price has outperformed,” McEvoy adds. “It goes back to their three circles philosophy — customers, employees and shareholders. They have done a phenomenal job of executing on that strategy in the upper Midwest.”

Dykema says Daniels and Atwell embodied those values when they started the bank rather than creating them through committee. “As a result, I would say the vision defines who they are as opposed to someone defining what they wanted the bank to be,” he says.

When the duo still worked for Associated, they gave Dykema his first loan to buy his first business in 1998. He is now CEO of Campbell Wrapper Corp. and Circle Packaging Machinery, which manufacture machinery that companies in the food, medical and pharmaceutical, and other industries use to package their products. When Atwell and Daniels left Associated, Dykema “transitioned over as quickly” as he could to become a customer of Nicolet. He joined the boards of both the bank and the holding company in 2006.

Atwell served as Nicolet’s chairman and CEO until April 2021 when he relinquished his CEO role and became the institution’s executive chairman. Daniels took on the chairman title last year, and Atwell continues to serve on the board as a director.

Dykema has always been struck by Daniels and Atwell’s ability to understand credit risk, starting with evaluating character and a business plan, and later the potential collateral. Back in the 1990s, Dykema noted that while he may have had alternatives when looking for that first loan, none of the options “would have felt like a partnership of someone believing in and betting on me. Other alternatives would have felt like getting a loan and the banker becoming an overseer rather than partner,” he says.

“Their willingness to take a risk on me in that situation was something that you don’t lose sight of. You don’t forget,” Dykema adds. “There are a lot of stories like mine within the northeast Wisconsin and northern Michigan communities, and all those communities are better [because of] them.”

Beyond the Green Bay community, Daniels is well respected with investors and the banking industry at large, McEvoy says. He is known for being a straight shooter who wants to be successful but also recognizes that it takes a team to achieve that, he adds. Daniels will be quick to talk up the abilities of other executives on the management team. “He is very supportive of the people around him.”

When asked what has driven Nicolet’s steady rise in Bank Director’s RankingBanking, Daniels is quick to say, “Our people.” He recognizes that it’s the employees who really make a difference in their communities and make the Nicolet brand matter to the far corners of the bank’s footprint. “You start a company in your basement. You have an idea, and it’s very driven around you,” he adds. “And the goal is to make sure it becomes less about you and more about a thousand people showing up and getting behind the brand … and figuring out what shared success and mattering means.”

Banking is an incredibly complex industry and difficult to succeed in. There are all of the regulations that institutions must follow, and a business model that is highly leveraged, funded by demand deposits that can disappear at any time. But something else haunts Daniels more than any of that.

“Someone once said, ‘What keeps you up at night?’ You know what that is? What if we stop mattering?”