How Consolidation Changed Banking in Five Charts

Over the past 35 years, few

secular trends have reshaped the U.S. banking industry more than consolidation.

From over 18,000 banks in the mid-1980s, 5,300 remain today.

Consolidation has created

some very large U.S. banks, including four that top $1 trillion in assets. The country’s

largest bank, JPMorgan Chase & Co., has $2.7 trillion in assets.

Historically, very large

banks have been less profitable on performance metrics like return on average

assets (ROAA) and return on average tangible common equity (ROTCE) than smaller

banks. The standard theory is that banks benefit from economies of scale as

they grow until they reach a certain size, at which point diseconomies of scale begin to drag down their performance.

This might be changing, according

to interesting data offered Keefe, Bruyette & Woods CEO Thomas Michaud in

the opening presentation at Bank Director’s 2020 Acquire or Be Acquired

conference. The rising profitability of large publicly traded banks and one of

the underlying factors can be seen in five charts from Michaud’s presentation.

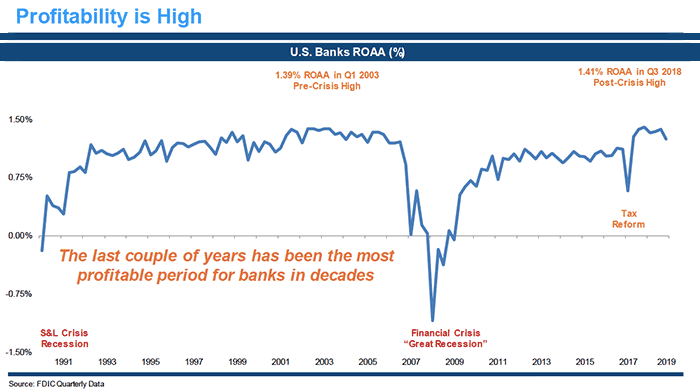

Profitability

Banking has been highly profitable since the early 1990s – except, of course, for that big dip starting in 2006 when earnings nosedived during the financial crisis. The industry’s profitability reached a post-crisis high in the third quarter of 2018 when its ROAA hit 1.41%. Keep in mind, however, this chart looks at the entire industry and averages all 5,300 banks.

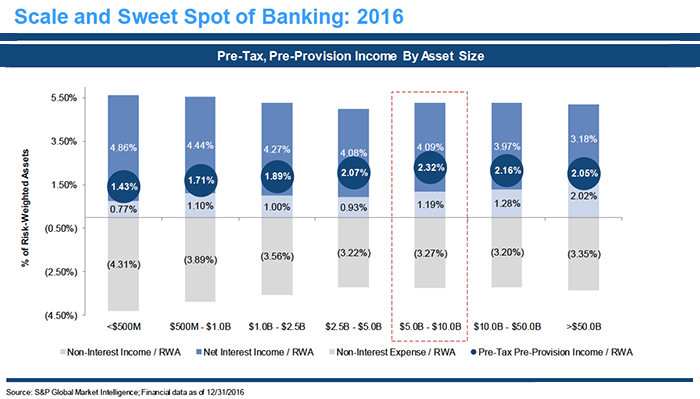

Sweet Spot of Profitability

Banking is also highly differentiated by asset size: many very small institutions at the bottom of the stack, four behemoths at the top. Michaud’s “sweet spot” in banking refers to a specific asset category that allows banks to maximize their profitability relative to other size categories. They have enough scale to be efficient but are still manageable enterprises. In 2016, this sweet spot was in the $5 billion to $10 billion asset category, where the banks’ pre-tax, pre-provision income was 2.32% of risk weighted assets.

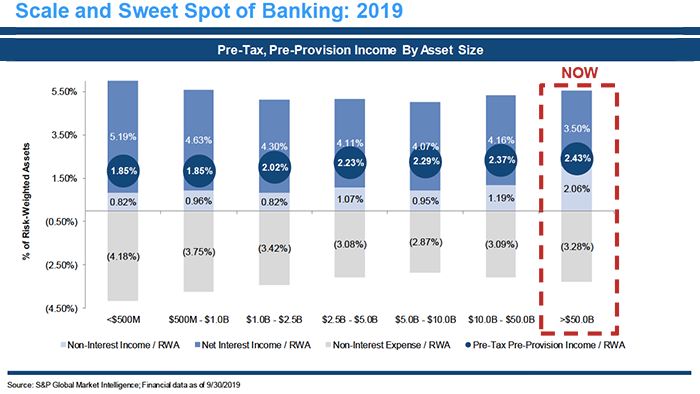

Sweet Spot Shifts

It’s a different story three years later. In 2019, the category of banks with $50 billion in assets and above captured the profitability sweet spot, with pre-tax, pre-provision income of 2.43% of risk weighted assets. What’s especially interesting about this shift is that, by my count, there are just 31 U.S. domiciled banks in this size category. (I excluded the U.S. subsidiaries of foreign banks, but included The Goldman Sachs Group and Morgan Stanley.) Of course, these 31 banks control an overwhelming percentage of the industry’s assets and deposits, so they wield disproportionate power to their actual numbers. But what I find most interesting is that as a group, the biggest banks are now the most profitable.

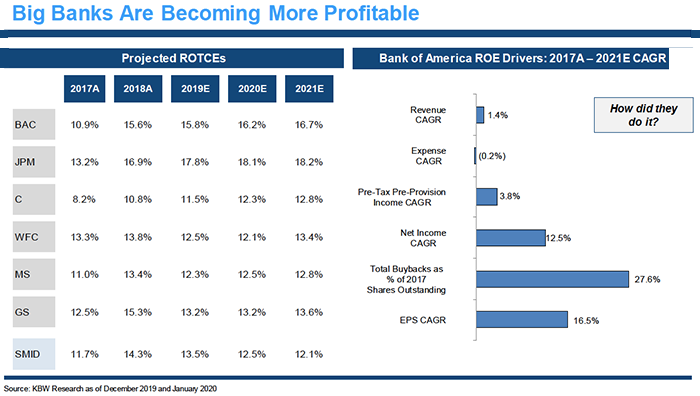

Big Bank Profitability

Even the behemoths have stepped up their game. You can see from the chart that KBW expects five of the six big banks – Bank of America Corp., JPMorgan, Wells Fargo & Co., Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs – to post ROTCEs of 12% or better for 2019. And some, like JPMorgan and Bank of America, are expected to perform significantly better. KBW expects this trend to continue through 2021, for the most part. What’s behind this improved performance? Buying back stock is one explanation. For example, between 2017 and 2021, KBW expects Bank of America to have repurchased 27.6% of its outstanding stock at 2017 levels. But there is more to the story than that.

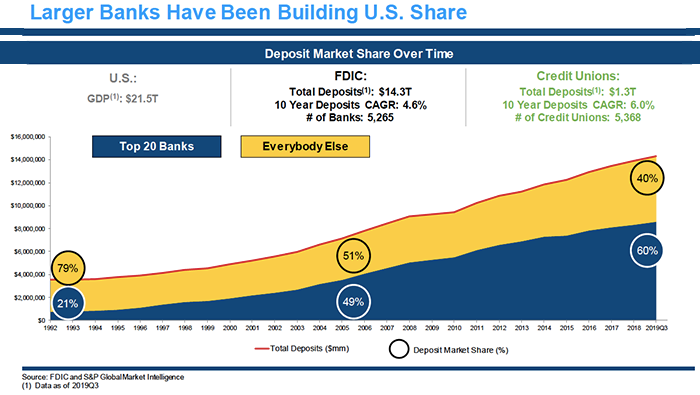

Taking Market Share

The 20 largest U.S. banks have aggressively grown their national deposit market share – a trend that seems to be accelerating. Beginning during the financial crisis in 2008, the top 20 began gaining market share at a faster rate than the rest of the industry. The differential continues to widen through at least the third quarter of last year. But the financial crisis ended over a decade ago, so a flight to safety can no longer explain this trend. Something else is clearly going on.

Consumers across the board are increasingly doing their banking through digital channels. Digital banking requires a significant investment in technology, and this is where the biggest banks have a clear advantage. Digital has essentially aggregated local deposit markets into a single national deposit market, and the largest banks’ ability to tap this market through technology gives them a significant competitive advantage that is beginning to drive their profitability.

Having too much scale was once a disadvantage in terms of performance – that may no longer be the case. Banking increasingly is becoming a technology-driven business and the ability to fund ambitious innovation programs is quickly becoming table stakes.