Editor-in-Chief Naomi Snyder is in charge of the editorial coverage at Bank Director. She oversees the magazine and the editorial team’s efforts on the Bank Director website, newsletter and special projects. She has more than two decades of experience in business journalism and spent 15 years as a newspaper reporter. She has a master’s degree in journalism from the University of Illinois and a bachelor’s degree from the University of Michigan.

An Ambitious CEO Drives Columbia’s Growth

*This feature is part of the 2025 RankingBanking report.

Clint Stein, the 53-year-old CEO of Columbia Banking System in Tacoma, Washington, admits he’s rarely content. “It’s just how I’m wired,” he says. “We don’t just sit on our hands and do nothing.”

Stein, logging into a video call in June, had just announced plans to acquire a second bank in three years. The first, a notoriously difficult merger of equals with Umpqua Holdings Corp., had dragged on for well over a year pending regulatory approval before its 2023 completion. Then, investors sent the stock plummeting about 30% after Columbia missed earnings expectations for the fourth quarter of 2023.

Still, the deal propelled $52 billion Columbia toward the top of Bank Director’s 2025 RankingBanking two years in a row for its asset size category. It ranked No. 2 among banks above $50 billion in assets for 2024, right behind No. 1 ranked East West Bancorp. For 2023 results, it ranked No. 5 for banks $50 billion and more.

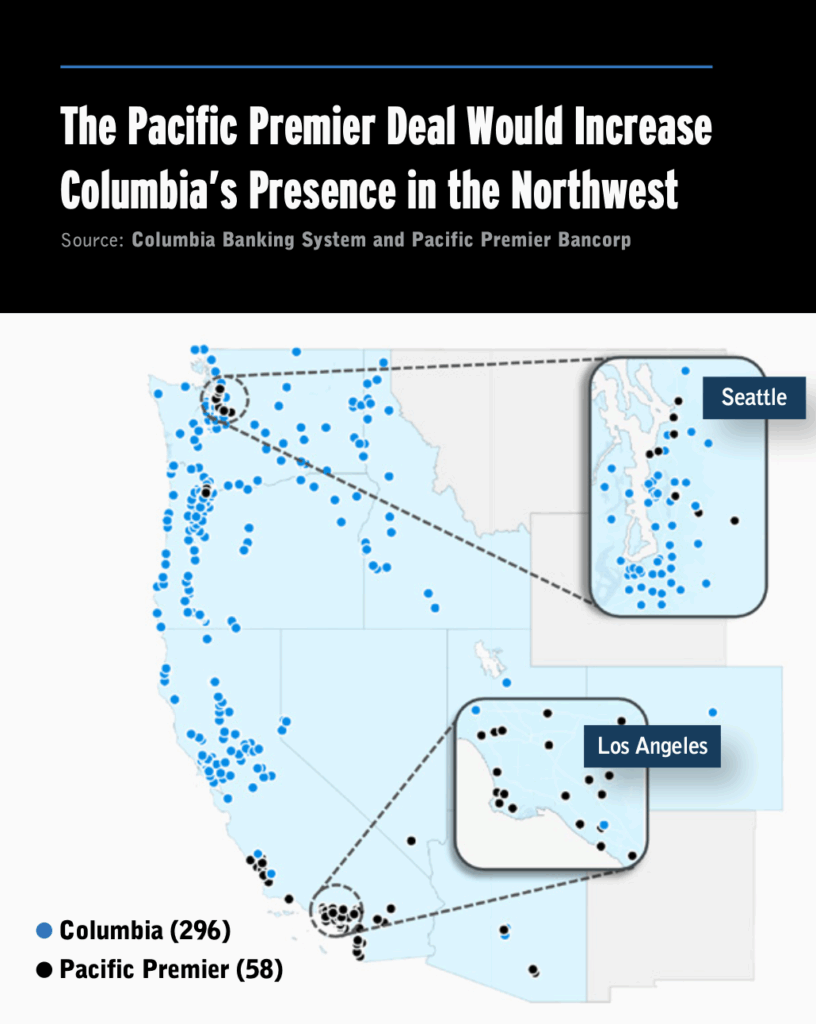

Now, Columbia is proposing a second transformative deal to acquire $18 billion Pacific Premier Bancorp in Irvine, California, for $2 billion in stock. Combined, the deals will more than double the size of the bank in three years to over $70 billion in assets and create a franchise that stretches from Washington state to Southern California with additional markets in the Southwest. Executives expect the latest deal to close in the second half of this year.

Stein and his executive team are pushing forward despite investor skepticism, with a strategic focus on creating long-term value rather than growth for its own sake. But will investors like the deal as much as they do?

A Solid Banking Franchise

Columbia traces its roots back to 1993, when W.W. “Bill” Philip sold Puget Sound Bancorp to KeyCorp and started another community bank. Later, Melanie Dressel, who had been a part of the original team to launch the bank, became CEO. She was famous for her “no jerk” rule — she pledged not to employ jerks at Columbia. She built market share in the Washington region by focusing on strong customer relationships and profitability, not growth for its own sake. But her goal was to double the size of Columbia to make sure the bank remained relevant no matter what happened in the industry, and Stein says he embraced that goal. “It wasn’t just about trying to get to a certain asset size, but it was about what would guarantee our relevancy,” he says.

Stein, who was CFO, became Dressel’s hand-picked successor. A few years after she died in 2017, Stein took over. His management team will tell you, he’s no jerk. “We’re a learning organization, and we’re going to make mistakes, but he’ll allow us to do that,” says Columbia’s Christopher Merrywell, president of consumer banking, who has worked with Stein for more than a decade. “And I think it’s part of his vision of creating better leaders.”

Others have a favorable view of Stein’s personality as well. “I think he’s certainly a high-character individual,” says Jeffrey Rulis, a managing director and senior research analyst at D.A. Davidson Cos. “He is a very team-oriented CEO. I think he looks to the strength of the team rather than one leader.”

Stein is a bit humble. He likes to joke that what made him an A student in math inherently made him a C student in English. “He’s got a very in-depth knowledge of the financials of the bank and what it takes for us to achieve our goals,” Merrywell says. Drew Anderson, chief administrative officer, describes him as focused on bottom-line results rather than top-line growth. In fact, the bank rarely dips below 1% return on assets. “There’s not a lot of guesswork in terms of what he wants us to become, which is great because it’s a clear direction,” Anderson says. “He’s hard-charging, but he knows what we can become.”

It’s not that Stein thinks the bank must always do M&A. But he does think the bank needs to grow to achieve efficiencies of scale and ensure the bank has the technology and capabilities to serve customers. “We’re in a consolidating industry, and scale matters,” he says.

Still, management seems to understand that rapid growth comes with certain risks. “We’ve seen banks that just grow for the sake of growth, and quadruple in size in three years, and that story never ends well,” Anderson says. Unlike some other regional banks that failed in the spring of 2023, Columbia’s business model is plain vanilla. It’s based on a diversified core deposit base, branch banking infrastructure, solid capital and credit, and little to no wholesale funding. “I think the chief credit officer [at Columbia] has used the word ‘boring’ when asked about credit, which is a good thing,” says Matthew Clark, managing director and senior research analyst for Piper Sandler & Co. “So yeah, credit has been pretty stable and benign for a number of quarters now. I don’t see that changing materially.”

A Deal Delayed

Stability was hard to maintain during the whole ordeal of the Umpqua merger. Umpqua CEO Cort O’Haver and Stein had gotten together to create one of the few large, independent banks in the Northwest, announcing their deal in October 2021. Stein would become CEO of the holding company and the bank, which would keep the name Umpqua. O’Haver would stay on as executive chairman. Mergers of equals are hard as it is. Regulators made it even harder.

Anderson believes the deal added a few gray hairs to his head. The stress began with the delays in regulatory approval, which make it hard to plan. “We had six different legal day-ones planned because of different scenarios we were hearing from our regulators, ‘Oh, it’s coming. Nope, it’s not,’” he says. Anderson, who came from the Umpqua side, co-lead the integration management office with a colleague from Columbia.

“It was pretty frustrating internally, because if you look at Umpqua standalone, Columbia standalone, two healthy banks, two banks that didn’t have any kind of regulatory issues that would’ve stopped a deal,” he says. “It was truly just the regulatory environment at the time was taking a very long time to even look at deals.”

Andrew Terrell, managing director and equity analyst for Stephens, says the long delay to close likely caused disruption for staff. “We heard anecdotally, there are other banks that hired teams away during that merger transition period,” he says.

When regulatory approval did come, it included the demand to divest branches before the merger’s close. After that, the bank moved forward with plans for a digital conversion on March 17, 2023. It was an inopportune time. Seven days before the digital conversion, Santa Clara, California-based Silicon Valley Bank failed amid a deposit run on the bank. Other banks were on edge. Anderson worried that the slightest hitch might spook customers into thinking that Umpqua was about to fail, even if it wasn’t. But delaying the integration could also create rumors about Columbia’s ability to combine the two banks. Anderson recalls that for a few weeks, he got about three or four hours of sleep per night.

He says the bank worked hard to minimize disruption for clients and staff, communicating regularly on the acquisition details. “We didn’t let things snowball into larger issues when we could have taken care of something earlier in the process,” he says. “It’s funny, the second you announce a deal … your competitors will now start marketing against you. … It’s on the bank to make sure that we keep that change as minimal as possible.”

Investor Skepticism

Investors also have been a tough sell. No doubt, purchase accounting from the Umpqua merger accounted for some of the outstanding performance on Bank Director’s RankingBanking — Columbia and Umpqua announced the deal when interest rates were low and closed it as rates moved higher. Assets were marked down at fair value at closing, which accretes over time in an earnings stream through net interest income, says Terrell. That amounted to $306 million in purchase-accounting earnings in 2024 on $1.7 billion of total net interest income, he says.

Also, the bank missed analyst expectations for earnings for the fourth quarter of 2023 by about 20%, making it hard for some investors to stomach the Pacific Premier deal. “We are wary of investor scrutiny,” wrote Rulis in an April note to clients. “The [Pacific Premier] deal is a different combination, of different size/scale, in a different operating environment … and should be treated on its own merits. However, the prior M&A overhang will mean [Columbia]’s execution this time around will have elevated scrutiny, in our view.”

For Stein’s part, he attributes the earnings miss in 2023 to rising deposit costs, a higher provision expense and the fact that the bank didn’t exclude from operating earnings the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.’s one-time special assessment to pay for the spring 2023 bank failures. Stein admits he was surprised by the magnitude of the stock market’s reaction to the earnings miss. His team decided to speed up previous plans to cut costs after the stock price fell. Within about 60 days, an undisclosed number of people were laid off.

Piper’s Clark says the management team cut more than $70 million in expenses in 2024, $20 million more than they had announced as part of the Umpqua deal. Columbia did so without using consultants, a point of pride for Stein. Bill Burgess, cohead of financial services for Piper Sandler, worked as Columbia’s investment banker on the Pacific Premier deal. He says it was typical of Stein’s style. “He was able to get done in about six weeks what McKinsey or Bain or others would take six months [to do],” Burgess says.

Plus, Columbia has been improving the balance sheet by reducing wholesale borrowings and getting rid of mostly brokered, multifamily loans inherited from Umpqua. As an example, Umpqua had a $4 billion multifamily loan division with only $17 million in deposits associated with it, Stein says. “So that’s just math that doesn’t work,” he adds.

As of June, Clark says Columbia put together four consistent, solid quarters since its fourth quarter 2023 earnings miss. “They’ve gotten more disciplined, more proactive on the deposit pricing side last year, and that’s helped their margin expand, which obviously enhances profitability.”

The Next Steps

The bank had four branches in Southern California from the Umpqua deal and also began opening de novo branches in places such as Phoenix and Salt Lake City. But it would take over a decade to gain the same type of density organically that it would achieve through the Pacific Premier deal, says Merrywell.

“And so, it made perfect sense,” Merrywell says. “Here’s a well-respected bank that goes to market very similar as we do. They’ve got a great capital ratio. It’s just a natural fit in a market that we’ve said we’re interested in. And it adds to a little bit more density into the Coachella Valley [and] into Arizona where we had started to expand as well.”

Growing meant the bank could serve larger customers while gaining market share among small businesses. “There’ll be very, very limited instances of companies that we can’t or shouldn’t bank,” Stein explains. Already, Umpqua Bank was the No. 1 Small Business Administration 7(a) program lender in Washington and Oregon in 2024, according to the SBA. Could it rank near the top in the rest of its markets?

Plus, the Pacific Premier deal has a better chance of success than the Umpqua merger, D.A. Davidson’s Rulis says. For one, the regulatory environment has changed, with the Trump administration signaling more willingness to approve deals and on a faster timeline. Because of that, analysts don’t expect delays in terms of getting the deal approved. Management said that Pacific Premier had the cleanest credit of any franchise Columbia has reviewed, Rulis says. Columbia would pay no premium in the stock transaction. Instead, Pacific Premier would own 30% of the combined institution. If the deal is a success, shareholders of both banks will benefit.

But the deal will certainly mark the end of an era. Not only will Pacific Premier go away, making room for a much larger independent franchise in the West, but the Umpqua name for the bank will also disappear, to be replaced by Columbia. Stein noted that the Umpqua name is hard to pronounce outside Oregon. “It’s a part of the state, it’s an ice cream, it’s a bank, it’s a river,” he explains. But now, when Stein goes to meet customers in Colorado or Arizona or Utah, they want to know what an Umpqua is, and Columbia is much easier to grasp. O’Haver, the former CEO of Umpqua, quietly left his position as executive chairman of the combined institution in March 2025, according to a bank filing.

Anderson says he’s motivating his staff based on the opportunities of a much larger organization. “I’m looking at celebrating my 15th-year anniversary this summer,” Anderson says. “And I’ve never been more optimistic, ever.”

The bank is moving beyond a difficult chapter with Umpqua’s merger. “It was a great experience,” Anderson says. “I’m so glad with the results. But we’re looking forward, knock on wood, to a smoother one this time around.”

*This article has been corrected to say Drew Anderson has spent 15 years with the bank.