Why Growth Matters for CRE Concentration Risk

Community banks are contending with the increasing risk profile of and regulatory scrutiny around commercial real estate (CRE) concentrations. Indeed, the regulatory community telegraphed in December 2015 their intentions of focusing bank examinations on concentration management, and since then, the FDIC has noted an increase in matters requiring board attention (MRBAs) associated with concentrated loan exposures. Additionally, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency raised its regulatory stance on CRE lending from “monitoring status” to “an area of additional emphasis.” To explain their renewed attention, the regulators cited intense loan growth, sharp rent-rate and valuation increases, competitive pressures and an easing in underwriting standards eerily similar to the lead-up to the Great Recession—during which many community bank failures were driven by construction & development (C&D) and CRE concentrations.

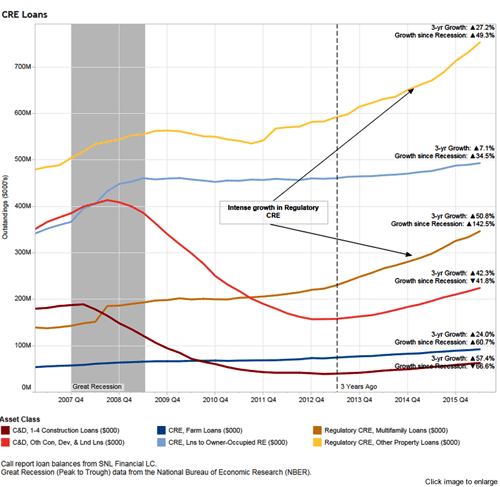

While there is evidence that this renewed attention has shifted many banks’ CRE underwriting stance to a net tightening position, this has yet to have a material impact on C&D and CRE loan outstandings. A trend analysis across all commercial and savings banks shows intense increases in both C&D and non-C&D regulatory CRE.

Growth Rates By Type of Asset for All Commercial and Savings Institutions

Note the sharp difference between C&D (red) and non-C&D Regulatory CRE (orange): the Great Recession saw a precipitous drop in C&D balances, but multifamily and other property (i.e., non-owner-occupied CRE) increased in total outstandings during and after the Great Recession with growth since the recession of 142.5 percent and 49.3 percent respectively.

It is constructive to highlight that growth rates—while sometimes overlooked—are explicitly part of the 2006 CRE regulatory guidelines. Those guidelines stipulate that an institution is only in excess of the CRE guideline if CRE as a percent of capital is greater than or equal to 300 percent and the institution’s CRE portfolio has increased by 50 percent or more during the prior three years.

The regulators have repeatedly pointed out that—unlike many other regulatory prescriptions and proscriptions—the CRE guidelines are not limits. The FDIC has noted that because “community banks typically serve a relatively small market area and generally specialize in a limited number of loan types, concentration risks are a part of doing business” and the OCC specifically caveated that the “guidance does not establish specific limits on CRE lending; rather, it describes sound risk management practices that will enable institutions to pursue CRE lending in a safe and sound manner.”

In this context, growth may be the most important element of the CRE guidelines because it quantifies the potential that portfolio size may outstrip the risk management infrastructure (spanning credit, capital, strategic, compliance and operational components) to support that lending. In cases of aggressive growth (whether you are above or below the other regulatory CRE criteria), it is that much more important to establish proactive and robust credit risk monitoring and management.

Luckily, as the CRE guidance is now quite mature, industry-wide best practices exist to aid in this exercise:

- Monitor the risk for all of your bank’s credit concentrations—not just CRE and C&D.

- Analyze and segment your entire portfolio by at least the “regulatory big three” of product, geography and industry. It is also constructive to slice-and-dice by vintage, underwriting bands, branch, etc.

- For each segment, calculate and monitor growth rates along with percent of risk-based capital and asset quality (and consider establishing management triggers and thresholds on these key risk indicators).

- Analyze your portfolio hierarchically so high-level trends are digestible for boards of directors while the detail can be drilled through so the results are tactically relevant to management and even individual loan officers. Banking is a relationship business, and risk analytics should lead to action that may start with a borrower conversation.

- Especially in the current relatively benign credit environment and in situations where loan growth may obfuscate asset quality deterioration, monitor leading indicators of risk like underwriting policy exceptions, loan review downgrades, covenant violations, valuation trends and average underwriting attributes.

- Perform portfolio and firm-wide loss stress testing to quantify the loss potential under hypothetical and severe conditions. Roll such stress test results through your balance sheet and income statement to assess the impact on earnings and capital adequacy.

- Where your portfolio analytics or portfolio-wide stress tests identify sensitive concentrations, perform loan-level stress testing.

- Incorporate credit concentration risk within your allowance for loan losses (ALLL)—remember that concentration risk is one of the nine subjective qualitative and environmental risk factors laid out by the 2006 Interagency Guidance on the ALLL and reaffirmed by FASB’s CECL standards update.