The Flawed Argument Against Community Banks

A few weeks ago, The Wall Street Journal published a story that struck a nerve with community bankers.

A few weeks ago, The Wall Street Journal published a story that struck a nerve with community bankers.

The story traced the travails of National Bank of Delaware County, or NBDC, a $375 million asset bank based in Walton, New York, that ran into problems after buying six branches from Bank of America Corp. in 2014.

It’s not that things were going great for NBDC prior to that, because they weren’t. Like many banks in small towns, it had to contend with stiff economic and demographic headwinds.

“As in other small towns that were once vibrant, decades of economic change altered the fabric of Walton,” Rachel Louise Ensign and Coulter Jones wrote in the Journal. “The number of area farms dwindled and manufacturing jobs disappeared.”

“Being located in, and serving, an economically struggling community could bring any bank down,” wrote Ron Shevlin, director of research at Cornerstone Advisors, in a follow-up story a week later.

NBDC hoped the branches acquired from Bank of America, for a combined $1 million, would revive its fortunes. But the deal only made things worse.

The branches saddled NBDC with higher costs and $12 million in added debt. Even worse, half the acquired deposits quickly went elsewhere, provoked by a poorly executed integration as well as, ostensibly, NBDC’s antiquated technology.

“Technology is causing strains throughout the banking industry, especially among smaller rural banks that are struggling to fund the ballooning tab,” Ensign and Jones wrote. “Consumers expect digital services including depositing checks and sending money to friends, which means they don’t necessarily need a local branch nearby. This increasingly means people are choosing a big bank over a small one.”

This echoes a common refrain in banking: that smaller regional and community banks can’t compete against the multibillion-dollar technology budgets of big banks—especially JPMorgan Chase & Co., Bank of America and Wells Fargo & Co.

Community bankers took issue with the article, Shevlin noted, because it seemed to portray the story of NBDC, which was acquired in 2016 by Norwood Financial Corp., as representative of community banks more broadly.

“This is so misleading,” tweeted Andy Schornack, president of Security Bank & Trust in Glencoe, Minnesota. “Pick on one under-performing bank to represent the whole.”

“Community banks are profitable and thriving,” tweeted Tanya Duncan, senior vice president of the Massachusetts Bankers Association. “Most offer technology that makes transactions seamless.”

Schornack and Duncan are right. One doesn’t have to look far to find community banks that are thriving, with many outperforming the industry.

A textbook example is Germantown Trust and Savings Bank, a $376 million asset bank based in Breese, Illinois.

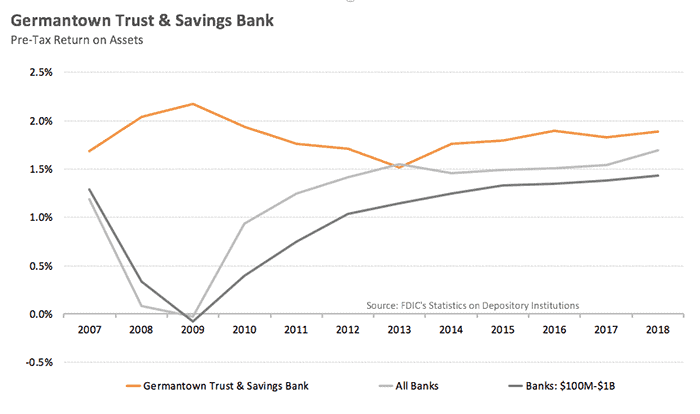

Germantown has generated a higher return on assets than the industry average in 11 of the past 12 years. The only exception was in 2013, when it generated a 1.52 percent pre-tax ROA, compared to 1.55 for the overall industry.

Germantown’s performance through the financial crisis was especially impressive. While most banks reported lower earnings in 2009, with the typical bank recording a loss, Germantown experienced a surge in profitability.

Germantown has gained local market share, too. Over the past eight years, its share of deposits throughout its four-branch footprint in Clinton County, Illinois, has grown from 27.8 percent up to 29.7 percent.

This is just one example among many community banks with a similar experience. For every community bank that’s ailing, in other words, you could point to one that’s thriving.

Yet, there’s another, more fundamental issue with the prevailing narrative in banking today. Namely, the data doesn’t support the claim that the biggest and most technologically-savvy banks are gobbling up share of the national deposit market.

In fact, just the opposite has been true over the past five years.

Let’s start with the big three retail banks—JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America and Wells Fargo—which are spending tens of billions of dollars a year on technology.

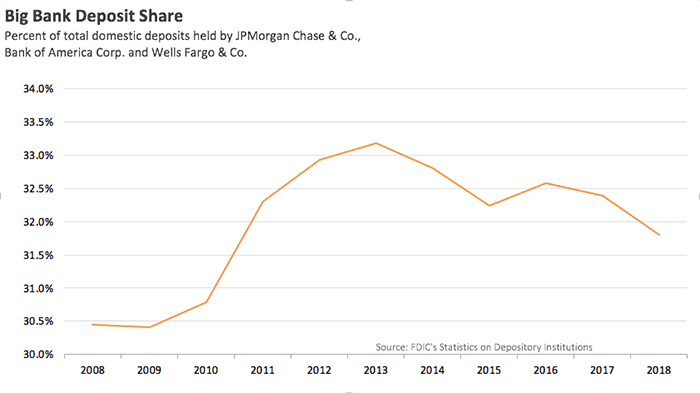

These three banks saw their combined share of domestic deposits swell in the wake of the financial crisis, climbing from 21.7 percent in 2007 up to 33.2 percent six years later. Since 2013, however, this trend has gone in the opposite direction, falling in four of the past five years. As of 2018, the three biggest banks in the country controlled 31.8 percent of total domestic deposits, a decline of 1.4 percentage points from their peak.

The same is true if you broaden this out to include the nine biggest commercial banks. Their combined share of domestic deposits has dropped from a high of 47.6 percent in 2013 down to 45.6 percent last year.

Given the number of branches many of these banks have shed over the past decade, it’s surprising they haven’t lost a larger share of domestic deposits. Nevertheless, it’s worth reflecting on the fact that, despite the gloomy sentiment toward community banks that’s often parroted in the press, their current and future fortunes are far from bleak.