How Credit Unions Pursue Growth

The nationwide pandemic and persistent economic uncertainty hasn’t slowed the growth of Idaho Central Credit Union.

The credit union is located in Chubbuck, Idaho, a town of 15,600 near the southeast corner, and is one of the fastest growing in the nation. It has nearly tripled in size over the last five years, mostly from organic growth, according to an analysis by CEO Advisory Group of the 50 fastest growing credit unions. It also has some of the highest earnings among credit unions – with a return on average assets of 1.6% last year – an enviable figure, even among banks.

“This is an example of a credit union that is large enough, [say] $6 billion in assets, that they can be dominant in their state and in a lot of small- and medium-sized markets,” says Glenn Christensen, president of CEO Advisory Group, which advises credit unions.

Unsurprisingly, growth and earnings often go hand in hand. Many of the nation’s fastest growing credit unions are also high earners. Size and strength matter in the world of credit unions, as larger credit unions are able to afford the technology that attract and keep members, just like banks need technology to keep customers. These institutions also are able to offer competitive rates and convenience over smaller or less-efficient institutions.

“Economies of scale are real in our industry, and required for credit unions to continue to compete,” says Christensen.

The largest credit unions, indeed, have been taking an ever-larger share of the industry. Deposits at the top 20 credit unions increased 9.5% over the last five years; institutions with below $1 billion in assets grew deposits at 2.4% on average,” says Peter Duffy, managing director at Piper Sandler & Co. who focuses on credit unions.

As of the end of 2019, only 6% of credit unions had more than $1 billion in assets, or 332 out of about 5,200. That 6% represented 70% of the industry’s total deposit shares, Duffy says. Members gravitate to these institutions because they offer what members want: digital banking, convenience and better rates on deposits and loans.

“The only ones that can consistently deliver the best rates, as well as the best technology suites, are the ones with scale,” Duffy says.

Duffy doesn’t think there’s a fixed optimal size for all credit unions. It depends on the market: A credit union in Los Angeles might need $5 billion in assets to compete effectively, while one in Nashville, Tennessee, might need $2 billion.

There are a lot of obstacles to building size and scale in the credit union industry, however. Large mergers in the space are relatively rare compared to banks – and they became even rarer during the coronavirus pandemic. Part of it is a lack of urgency around growth.

“For credit unions, since they don’t have shareholders, they aren’t looking to provide liquidity for shareholders or to get a good price,” says Christensen.

Prospective merger partners face a host of sensitive, difficult questions: Who will be in charge? Which board members will remain? What happens to the staff? What are the goals of the combined organization? What kind of change-in-control agreements are there for executives who lose their jobs?

These social issues can make deals fall apart. Perhaps the sheer difficulty of navigating credit union mergers is one contributor to the nascent trend of credit unions buying banks. A full $6.2 billion of the $27.7 billion in merged credit union assets in the last five years came from banks, Christensen says.

Institutions such as Lakeland, Florida-based MIDFLORIDA Credit Union are buying banks. In 2019, MIDFLORIDA purchased Ocala, Florida-based Community Bank & Trust of Florida, with $743 million in assets, and the Florida assets of $675 million First American Bank. The Fort Dodge, Iowa-based bank was later acquired by GreenState Credit Union in early 2020.

The $5 billion asset MIDFLORIDA was interested in an acquisition to gain more branches, as well as Community Bank & Trust’s treasury management department, which provides financial services to commercial customers.

MIDFLORIDA President Steve Moseley says it’s probably easier to buy a healthy bank than a healthy credit union. “The old saying is, ‘Everything is for sale [for the right price],’” he says. “Credit unions are not for sale.”

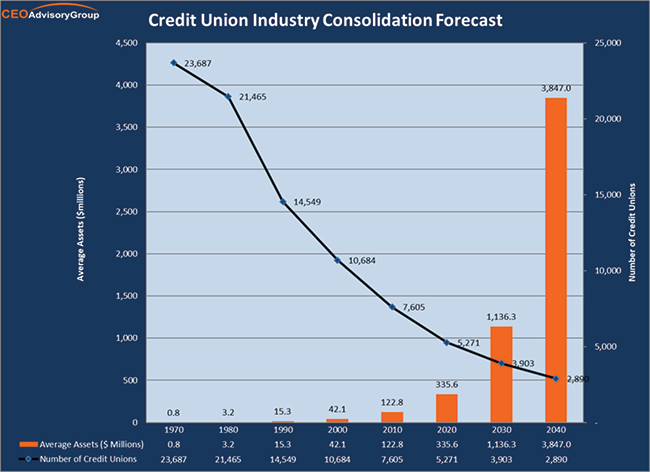

Still, despite the difficulties of completing mergers, the most-significant trend shaping the credit union landscape is that the nation’s numerous small institutions are going away. About 3% of credit unions disappear every year, mostly as a result of a merger, says Christensen. He projects that the current level of 5,271 credit unions with an average asset size of $335.6 million will drop to 3,903 credit unions by 2030 – with an average asset size of $1.1 billion.

CEO Advisory Credit Union Industry Consolidation Forecast

The pandemic’s economic uncertainty dropped deal-making activity down to 65 in the first half of 2020, compared to 72 during the same period in 2019 and 90 in the first half of 2018, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence. Still, Christensen and Duffy expect that figure to pick up as credit unions become more comfortable figuring out potential partners’ credit risks.

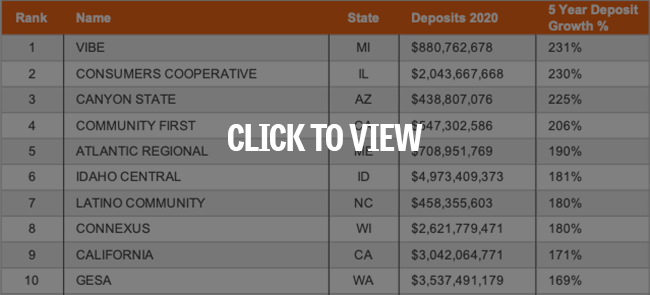

In the last five years, the fastest growing credit unions that have more than $500 million in assets have been acquirers. Based on deposits, Vibe Credit Union in Novi, Michigan, ranked the fastest growing acquirer above $500 million in assets between 2015 and 2020, according to the analysis by CEO Advisory Group. The $1 billion institution merged with Oakland County Credit Union in 2019.

Gurnee, Illinois-based Consumers Cooperative Credit Union ranked second. The $2.6 billion Consumers has done four mergers in that time, including the 2019 marriage to Andigo Credit Union in Schaumberg, Illinois. Still, much of its growth has been organic.

Canyon State Credit Union in Phoenix, which subsequently changed its name to Copper State Credit Union, and Community First Credit Union in Santa Rosa, California, were the third and fourth fastest growing acquirers in the last five years. Copper State, which has $520 million in assets, recorded a deposit growth rate of 225%. Community First , with $622 million in assets, notched 206%. The average deposit growth rate for all credit unions above $500 million in assets was 57.9%.

CEO Advisory Group Top 50 Fastest Growing Credit Unions

“A number of organizations look to build membership to build scale, so they can continue to invest,” says Rick Childs, a partner in the public accounting and consulting firm Crowe LLP.

Idaho Central is trying to do that mostly organically, becoming the sixth-fastest growing credit union above $500 million in assets. Instead of losing business during a pandemic, loans are growing – particularly mortgages and refinances – as well as auto loans.

“It’s almost counterintuitive,” says Mark Willden, the chief information officer. “Are we apprehensive? Of course we are.”

He points out that unemployment remained relatively low in Idaho, at 6.1% in September, compared to 7.9% nationally. The credit union also participated in the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program, lending out about $200 million, which helped grow loans.

Idaho Central is also investing in technology to improve customer service. It launched a new digital account opening platform in January 2020, which allows for automated approvals and offers a way for new members to fund their accounts right away. The credit union also purchased the platform from Temenos and customized the software using an in-house team of developers, software architects and user experience designers. It purchased Salesforce.com customer relationship management software, which gives employees a full view of each member they are serving, reducing wait times and providing better service.

But like Idaho Central, many of the fastest growing institutions aren’t growing through mergers, but organically. And boy, are they growing.

Latino Community Credit Union in Durham, North Carolina, grew assets 178% over the last five years by catering to Spanish-language and immigrant communities. It funds much of that growth with grants and subordinated debt, says Christensen.

Currently, only designated low-income credit unions such as the $536.5 million asset Latino Community can raise secondary capital, such as subordinated debt. But the National Credit Union Administration finalized a rule that goes into effect January 1, 2022, permiting non-low income credit unions to issue subordinated debt to comply with another set of rules. NCUA’s impending risk-based capital requirement would require credit unions to hold total capital equal to 10% of their risk-weighted assets, according to Richard Garabedian, an attorney at Hunton Andrews Kurth. He expects that the proposed rule likely will go into effect in 2021.

Unlike banks, credit unions can’t issue stock to investors. Many institutions use earnings to fuel their growth, and the two measures are closely linked. Easing the restrictions will give them a way to raise secondary capital.

A separate analysis by Piper Sandler’s Duffy of the top 263 credit unions based on share growth, membership growth and return on average assets found that the average top performer grew members by 54% in the last six years, while all other credit unions had an average growth rate of less than 1%.

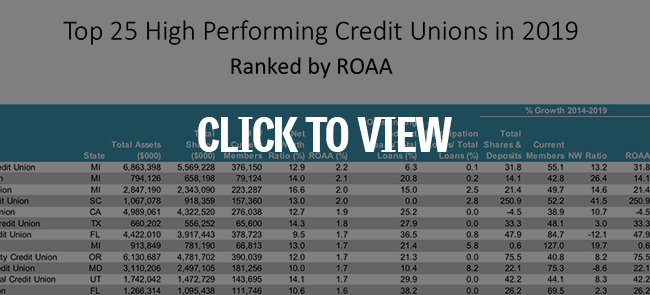

Many of the fastest growing credit unions also happen to be among the top 25 highest earners, according to a list compiled by Piper Sandler. Among them: Burton, Michigan-based ELGA Credit Union, MIDFLORIDA Credit Union, Vibe and Idaho Central. All of them had a return on average assets of more than 1.5%. That’s no accident.

Top 25 High Performing Credit Unions

Credit unions above $1 billion in assets have a median return on average assets of 0.94%, compared to 0.49% for those below $1 billion in assets. Of the top 25 credit unions with the highest return on average assets in 2019, only a handful were below $1 billion in assets, according to Duffy.

Duffy frequently talks about the divide between credit unions that have forward momentum on growth and earnings and those who do not. Those who do not are “not going to be able, and have not been able, to keep up.”