Low Interest Rates Threaten Banks — But Not the Way You Think

The coronavirus pandemic laid bare the struggles of average Americans – middle class and lower-income individuals and families. But these struggles are an ongoing trend that Karen Petrou, managing partner of the consulting firm Federal Financial Analytics, tracks back to monetary policy set by the Federal Reserve since the financial crisis of 2008-09.

In short, she says, the Fed bears some of the blame for the widening wealth gap, which sees the rich getting richer, the poor getting poorer and the middle class slowly disappearing. And that’s an existential threat to most financial institutions.

“The bread and butter of community banks – urban, rural, suburban – is the middle class and the upper-middle class, as well as the health of the communities [banks] serve,” Petrou explains to me in a recent interview. Even for banks focused on more affluent populations, the health of their communities derives from everyone living and working in it. “When you have a customer base that is really living hand to mouth,” she says, “that’s not a growth scenario for stable communities, or of course, [a bank’s] customer base.”

A lot of digital ink has been spilled on inequality, but Petrou’s analysis – which you’ll find in her book, “Engine of Inequality: The Fed and the Future of Wealth in America,” is unique. She explores how misguided Fed policy fuels inequality, why it matters, and how she’d recraft monetary policy and regulation. And she believes the future is bleak for banks and their communities if changes don’t occur.

Her ideas have the attention of industry leaders like Richard Hunt, CEO of the Consumer Bankers Association. “She’s not what I’d consider an activist or someone who has an agenda,” he says. “She is purely facts-driven.”

Central to the inequality challenge is the ongoing low-rate environment. We often talk about the Fed’s dual mandates – promoting maximum employment and price stability – but Petrou points out in her book that setting moderate rates also falls under its purview.

Low rates have pressured banks’ net interest margins for over a decade, but they’ve squeezed the average American household, too. Petrou writes that these ultra-low rates have failed to stimulate growth. They’ve also “made most Americans even worse off because trillions of dollars in savings were sacrificed in favor of ever higher stock markets.”

The Fed’s preoccupation with markets over households, she says, benefits the most affluent.

Low interest rates, as we all know, lower the returns one earns on safer investments, like money market accounts or certificates of deposit. That drives investors to the stock market, driving up valuations. Excepting a brief blip early in the pandemic, the S&P 500, Dow Jones Industrial Average and Nasdaq have all performed well over the past year, despite high unemployment and economic closures.

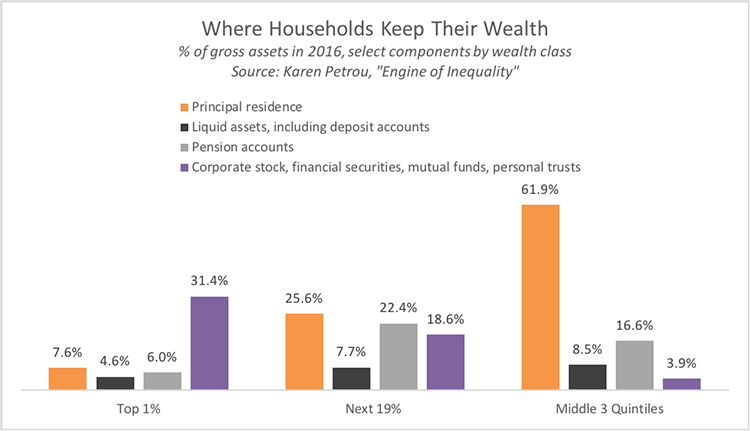

However, stock ownership is concentrated in the hands of a few. As of the fourth quarter 2020, the top 1% hold 53% of corporate equity and mutual fund shares, according to the Federal Reserve; the bottom 90% own 11% of those shares. Most of us would be better off, Petrou concludes, earning a safe, living return off the money we manage to sock away.

More than 60% of middle-class wealth is tied up in their homes; pension funds account for another 17%. Those have been underfunded, “but even underfunded pensions have a hope of paying claims when interest rates are enough above the rate of inflation to ensure a meaningful return on investment,” she writes.

And while homes account for a huge portion of middle-class wealth, home ownership has actually declined over the past two decades among adults below the age of 65, according to a Harvard University study. The supply of lower-cost homes has dwindled, and banks are reticent to make small mortgage loans, which are costly to underwrite. And for those who already own a home, prices still haven’t reached the levels seen before the financial crisis – in real dollars, they’re not worth what they once were.

And homes aren’t a liquid asset. Middle class Americans used to hold more than 20% of their assets in deposit accounts, but that’s declined dramatically. All told, low interest rates severely punish savers, who actually lose money when one adjusts for inflation.

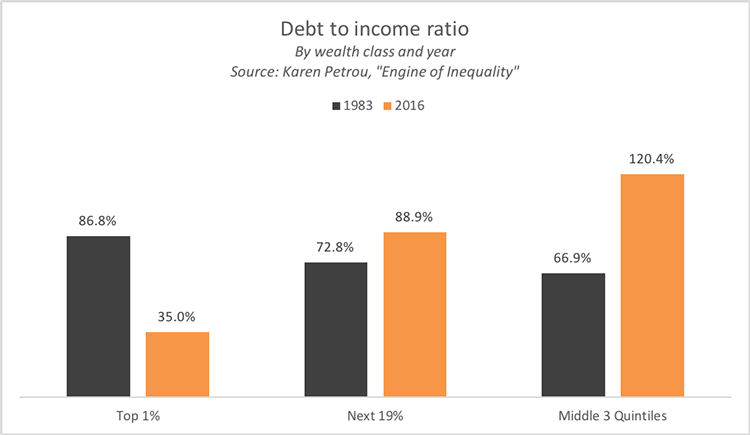

Average real wages haven’t budged in decades – but the costs for everything else have risen, from medical expenses to childcare to education and housing. So, what’s paying for all that if savings yield little and incomes are stagnant? Debt. And a lot of it, at least for the middle class, whose debt-to-income ratio has grown to a whopping 120% – almost double what it was in 1983. For the top 1%, it’s more than halved, to 35% of income.

Middle class households were in survival mode before the pandemic hit, explains Petrou.

“All of the Fed’s monetary-policy thinking is premised on the view that ultra-low rates spur economic growth, but most low-cost debt isn’t available to lower-income households, and most middle-income households are already over their head in debt,” she writes. “Monetary policy has failed in part because the Fed failed to understand America as it bought, saved and borrowed.”

Debt can be wonderful; it can build businesses and make buying a home possible for many. But that dream is disappearing. Coupled with the regulatory regime, low interest rates have changed traditional banking, explains Petrou. Financial institutions are forced to chase fee income, found in wealth management and similar products and services. And lending to more affluent customers makes better business sense.

Petrou wants the Fed to gradually raise rates to “ensure a positive real return.” Combined with other factors, rising rates would “make saving for the future not just virtuous, but successful,” she writes, “giving families with growing wages in a more productive economy a better chance for wealth accumulation, intergenerational mobility, and a secure retirement.”

It won’t fix everything, but it will help middle and lower-income families save for their homes, save for college and even pay down some of that debt.

Petrou is clear – in her book and in my interview with her – that the Fed isn’t ill-intentioned. But the agency is ill informed, she believes, relying on aggregate data that doesn’t reflect a full picture of the economy.

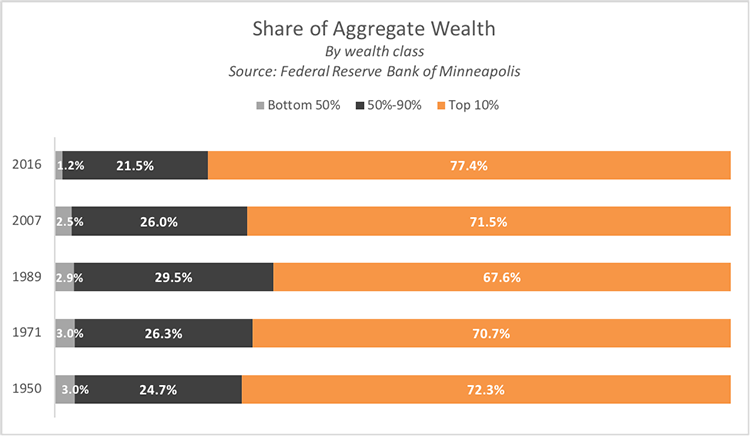

“The economy we’re in is not the one in which most of us grew up,” she says, referring to the baby boomers who form the majority of bank boards and C-suites. The top 10% hold a much greater share of wealth, and that share is growing. The things that many boomers took for granted, she says, are increasingly unattainable, or require an unsustainable debt burden.

College tuition offers a measurable example of how much things have changed. Adjusted for 2018-19 dollars, baby boomers paid an average $7,719 a year to attend a four-year public college, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Generation Z is now entering college paying roughly 2.5 times that amount – contributing to the growing volume of student loans.

“Assuming that [the economy] works equitably because there’s a large middle class means that banks will make strategic errors, misunderstanding their customers and communities,” Petrou tells me. “And that the Fed will make terrific financial policy mistakes.”