Get the Accounting Right: Valuing Core Deposit Intangibles in an Acquisition

The value of core deposit intangibles (CDIs) acquired in an acquisition is on the rise. When I first wrote about this topic in October 2012, I found that CDIs had declined in value as interest rates stayed low. The opposite is occurring now.

As a refresher, a CDI asset arises when a bank has a stable deposit base of funds from long-term customer relationships. CDI values derive from those customer relationships that provide a low-cost source of funding. CDIs are common assets, as most banks have some level of stable depositors to whom they pay interest at a rate lower than the rate they pay alternative funding sources. CDIs are important for bank boards to understand in an acquisition or sale, because they are the most common recorded intangible asset in a bank or branch acquisition. Boards can get in trouble if this asset is valued incorrectly, as it can impact future earnings.

Core Deposit Values

We compiled the values for CDIs using publicly available data on completed whole-bank and Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.-assisted bank transactions for the period of Jan. 1, 2013, through Oct. 3, 2014. To calculate the ratio of CDIs to core deposits, we aggregated the following deposit types to compute the bases:

- Noninterest-bearing demand deposit accounts (DDAs)

- Interest-bearing DDAs

- Savings accounts

- Money market accounts

Here is what we found:

| Quarter | Average CDI% |

| Q1 2013 | 1.19 |

| Q2 2013 | 1.19 |

| Q3 2013 | 1.93 |

| Q4 2013 | 1.72 |

| Q1 2014 | 1.61 |

| Q2 2014 | 1.34 |

| Q3 2014 | 1.73 |

| Q4 2014 | 1.92 |

| Overall Average | 1.54 |

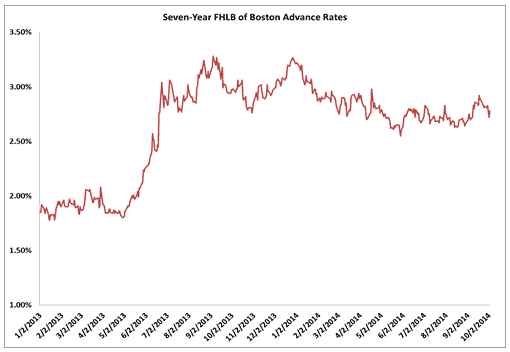

CDI values have increased from when I first wrote about this issue in October 2012, primarily because the long-term forecasts for interest rates have been increasing and the sources of alternative funds assumed have increased. For example, the following chart indicates the rates for seven-year Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLB) advance rates over the same time frame. Although using a single interest rate to value CDIs is a reasonable proxy for alternative funding, it is a simplistic view of how these rates are typically constructed.

Source: Data compiled from public filings

Useful Lives and Amortization Methods

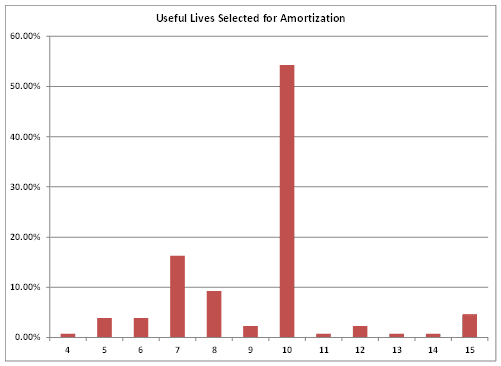

The Financial Accounting Standards Board guidance provides that if an income-based method is used to develop the value of the intangible asset, the period of projected cash flows should be considered when choosing a useful life. Another source of guidance comes from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), which publishes the Bank Accounting Advisory Series on various accounting issues. In its most recent guidance, the OCC indicated that in most cases, the useful life for CDIs wouldn’t exceed 10 years, although exceptions could be possible. Because banks file call reports on the basis of U.S. generally accepted accounting principles, the ultimate decision rests with the bank in consultation with its external audit firm.

The majority of acquiring banks chose 10 years as a useful life, as illustrated in the following chart for completed acquisitions from Jan. 1, 2013, through Oct. 3, 2014.

Source: Data compiled from public filings

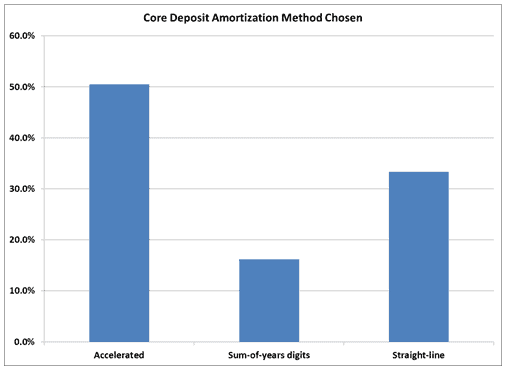

The method of amortization is another important component of recognizing expense related to CDI through the income statement. The method of amortization for any finite-lived intangible asset is influenced by Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) 350-30-35-6, which states that “the method of amortization shall reflect the pattern in which the economic benefits of the intangible asset are consumed or otherwise used up. If that pattern cannot be reliably determined, a straight-line amortization method shall be used.” The most prevalent method used was accelerated (either sum-of-years digits or some other method of acceleration), as illustrated in the following chart.

As banks plan transactions and consider what assumptions to use for modeling an acquisition, they should consider how the CDI will be calculated and the current level of CDI values. Acquirers that do not adequately consider the ultimate resulting value often find their future earnings to be below the levels projected in their acquisition modeling because they didn’t apply up-to-date assumptions. Reviewing available data should help acquirers better understand what policies are being used.

Source: Data compiled from public filings

Considering CDIs

As banks plan transactions and consider what assumptions to use for modeling an acquisition, they should consider how the CDI will be calculated and the current level of CDI values. Acquirers that do not adequately consider the ultimate resulting value often find their future earnings to be below the levels projected in their acquisition modeling because they didn’t apply up-to-date assumptions. Reviewing available data should help acquirers better understand what policies are being used.